Know Going Back

From found objects to monumental clay pipes, Tom Franco moves between sculpture, storytelling, and community with ease. Splitting time between Oakland and LA, he builds big, plays loose, and treats every project as a chapter in an ever-evolving narrative that folds friends, places, and wild ideas into the mix.

You studied at both UCSC and CCA – two very different creative environments. How did each shape your instincts as an artist?

It’s an interesting comparison. Santa Cruz came first, and I already knew I wanted to study art and be an artist. My late, great first sculpting teacher, Bill Iaculla, gave me the visual example of a sculptor’s life, pre-college, and introduced me to the medium of found objects. That hooked me right away. Any time I saw pictures of active sculptor studios, I knew I spoke the language – which is why publications like this one are so important. I find sculptors can sometimes get lost in the weeds unnecessarily, which is a terrible thing to wish for going into this.

UCSC had a new welding department facility, and that’s where I ended up spending my favorite time – culminating in my senior year making larger-than-life metal imaginative creatures. That was back in 2002, and there was no graduate program at the time, so I floundered for another year before finding my way to Oakland, where I’ve been ever since. With my wife and baby, we now split time between Oakland and LA.

What California College of the Arts gave me was a community of people who had taken the leap to attend full-time art school, some great teachers like John Toki and Arthur Gonzalez, and my personal jump from metal into ceramics. I never seem to let a good medium go once the spark is lit – so even while making ceramic sculptures, I was using mixed media to scale up faster. The Oakland ceramic campus gave me a few beautiful gifts that still define my approach today – working collaboratively in the moment with other visual artists; finding a marriage between steel welding and clay, each acting as a perfect medium with its liquid form as the glue; and discovering the clay revolutionary movement of the late 1950s, later known as Funk Ceramics.

Art school was also where I first hatched the idea and desire to open my own community art studio venture – the Firehouse Art Collective. Sticking together allowed me to keep a studio after school, and my most consistent accomplishment as an artist has been taking over beautiful buildings and inviting artists to rent studio space. Without a physical location, nothing seems to stick. This has been going for 21 years now, across 10 different locations.

“I often weave ten works from a series into one narrative, pairing three to five influences to see what new story emerges.”

The large ceramic pipes came into your practice a few years back – what was it about that form and process that intrigued you?

Mission Clay Arts and Industry has been running for 49 years as a kind of alternative-style residency program with no real rules – other than, once in a while, throwing artists of any background into deep creative waters to see if they can swim. Off to the side of a huge industrial factory is an art studio, while the main floor pumps out eight-foot-tall sections of water pipes built to survive underground for city infrastructure.

These pipes have walls so thick I can barely make a C shape with my fingers over the lip, and they’re wide enough that I can’t wrap my arms around them. In the wet state, fresh from the three-story extruder and standing vertically, if one fell on someone, it could kill them. Punch the wet clay wall with full force, and you’d break your hand.

Making art with these forms was intimidating, to say the least. I brought four people with me to tackle making twelve pipes over about a year and a half, across three visits. The goal was a show at the Arizona State University Ceramics Research Center and Archive, and since then, we’ve installed them at various public venues around the Bay Area.

Working on something larger than life, on a huge chunk of ceramics, felt like graduating into a club very few people get to join. This kind of work isn’t done in isolation – it starts to feel like making a feature film or competing in high-level sports, where people’s best abilities come out.

I’ve become fascinated with what it takes for artists to work on this scale, especially without the extruded pipe form as a base. The 1950s ceramic revolution had a big branch of artists experimenting with immense, free-form ceramic sculptures – wild and unbound. The Mission Clay directors come directly from that lineage and are still pushing the boundaries of what’s possible in clay today.

And the pipe form itself is mesmerizing. It’s a shape that’s everywhere in daily life without us really noticing. Certain forms are the backbone of how we experience art – like the rectangular canvas for most paintings, or the ceramic cup every potter makes and reinvents, or even the invention of the wheel, or the concept of zero. Stretch that circular form into 3D, and you get the pipe – the shape we’re working with at the factory.

Are there any ceramic pieces or artists you keep returning to for inspiration? What is it about their work that speaks to you?

I’m a big believer in not copying, but paying homage to my favorite artists in my own work. Most of the time, I create out of pure enjoyment – the impulse to make something with my hands. If the work starts to feel boring, too predictable, or bound by expectations of how it’s “supposed” to look, I mentally reject it.

I love drawing alongside kids because the spontaneity is so high and the clarity of ideas is so sharp – though yes, there’s the cleanup factor. That goes for adults, too. Over the years, I’ve developed tricks to get into the creative zone depending on my mood.

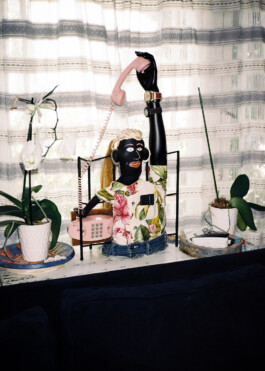

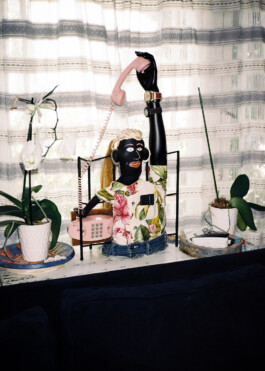

Collecting found objects is my primary one. I imagine what they could become in a second or third life. Collaboration is another – returning again and again to my favorite artist peers, as if we’re in a band. I use mixed media to heighten the sculptural quality of the work, often with industrial epoxy. And whenever possible, I incorporate other artists’ work into mine. That began with anonymous pieces rescued from the trash, and evolved into using works by friends and known artists as part of my own narratives.

Sometimes I’ll depict an art hero making their own work – like my small ceramic scene of Viola Frey in her CCAC studio, surrounded by three of her 13-foot figures, done loosely in her style. Or painting Sister Gertrude Morgan’s imagery as miniature canvases on the walls of my own sculptures – her life with Jesus, angels, and community scenes, reinterpreted through my hand.

This past year I made a miniature clay portrait of Jackson Pollock wearing a full-sized motorcycle helmet, crossed with metal pieces on top, each capped with tiny beer bottles at the corners, with colorful strings running into his mouth – a playful nod to a beer-guzzler party hat. I did it because I love Jack’s work, and it gave me a way to spend more time with him. I’m drawn to innovators who push ideas in unexpected ways.

Because the work transforms so much in my hands, I’m never too concerned about “copying.” It’s about combining sources to create something entirely new. Each sculpture might carry three to five influences, and then I often weave ten or so finished works into a single storybook narrative. Working this way, a new visual story always emerges.

And I should mention my mentor, John Toki, who continually inspires me – not only through his monumental free-standing clay works, but also through his deep commitment to community building and service to other artists.

“As a little kid, my mom once let me spend my $2 allowance on some random plumbing hardware simply because it ‘looked cool.’”

Toys and found objects often show up in your work as playful characters. What draws you to them – and what do you love about telling stories that way?

Part of it is the joy of collecting. I once worried that, as an adult, I’d never again feel the thrill of buying a toy and playing with it like I did as a kid – until I realized I could incorporate all those things into sculptures. That wall just lifted, and suddenly everything was fair game again.

It works both ways, too. As a little kid, my mom once let me spend my $2 allowance on some random plumbing hardware simply because it “looked cool.”

The same goes for objects tied to habits I’ve since given up – like alcohol and smoking paraphernalia. For example, I’ve glued beer and liquor bottles into my work. I have a series of beer steins with narratives sculpted into the sides, each topped with a second beer bottle that continues the original story in paint.

As someone who studies vessel forms, I often fill them with sculptural shapes – whether built from my own cups or someone else’s finished pieces. I might take wet clay and build an upside-down cup, or what I call a “mountain form,” then tell a story in medium relief around the surface.

Much of this process circles back to storytelling – sometimes about my own life, sometimes about the objects themselves. My brain works like a detective searching for visual clues in an object, until fantasy takes over. I sometimes wonder if it’s all one long, ongoing story that I keep expanding with each new piece.

In many ways, I think that’s true. When I’m feeling particularly ambitious, I try to define the world these works are coming from. Maybe it’s half about unlocking my own psyche and consciousness, step by step, to get closer to being free.

You split your time between Oakland and Los Angeles – how does each city influence the way you work, think, or build community?

I grew up in Palo Alto, then moved to the East Bay and quickly realized most of the artists were there. Only through travel and hindsight do I see how unique that was. The arts community in Oakland and Berkeley has immersed me in an ongoing creative process – people are so generous, willing to go to any length to make their work, and I find that endlessly inspiring.

That said, I can’t just stay insulated in one place. Los Angeles is a massive, professional city that expands my horizons and connects me to a much broader network. The systems in LA are uniquely set up to reach the world – and to be accessible to everyone.

I love the exchange between the two. There’s a beauty in bringing the community spirit of the East Bay to LA – and then carrying the broader expertise back to the East Bay, reaching even more people.

“My brain works like a detective searching for visual clues in an object, until fantasy takes over.”

Alongside guitars, you’ve also used skateboards as canvases – how do these unexpected surfaces shape the stories you want to tell?

I’m not the first to paint on guitars or skateboards, but it’s still something you don’t see too often. Skateboard decks are made from the best, most durable plywood out there – if there were a way to access a full 4' x 8' sheet that would be crazy cool, but no one makes that, and it would be insanely expensive. In comparison, I often get skateboard decks for free.

Just painting on a flat deck isn’t usually enough for me to get into a creative zone. I like to sketch a story, cut the edges into a more three-dimensional shape, and then paint it in. That way I’m engaging my sculptural mind while painting.

I think artists tend to either think in 2D or 3D – and it shows in their work. Some sculptors never touch color, and some painters never touch form. I bounce between the two, but I have to prepare myself for each because they come from different moods and thought patterns.

Other surfaces I’ve worked with include handsaws, basketballs and soccer balls (inflated or deflated), chairs, shoes, bottles, cups, the human face, and the human form. The narratives that come out of these shapes are often – abstract self-portraits from the inside out, groups of people, kids, sports in action, artists making art, meditators learning meditation, and animals acting like people: frogs, dogs, aliens, snakes, rabbits, big cats, flowers. And sometimes animals acting like animals – birds, dolphins, turtles, alligators, horses.

Right now I’m working on a series of two-legged walking dinosaurs, each seven feet tall, made from a single road bike, strategically cut and welded back together as if they were dinosaur bones. Their triangular bodies have shelves built into them that hold buildings loosely formed by hand out of clay. The clay is a special cone 15 body that dries quickly, cracks all over, and still holds its form – I love it. Inside the buildings live small communities, visible through the windows, nurturing trees. These dinosaurs roam high above the earth in their own microcosm of dino-pod life, waiting to stumble upon another kind of community out there.

How did the Know Going Back tour come together? Where’d the bus come from, and how were the artists chosen?

In 2021, I was invited to show work at the Canton Museum in Ohio. They gave me my own room and needed everything finished in advance so they could plan and promote. The challenge? Getting the work from California to Ohio on a shoestring budget.

Usually, I’d arrive early and make the work on site, turning it into a kind of traveling residency. Since that wasn’t an option, I decided to drive the work myself. Friends started jumping on board, and as we mapped the route, we realized how many great art stops we could make along the way. It snowballed into a formal tour – eight to ten artists at different stops – and we called ourselves The Grateful 8 to 10. Every six hours, we had a venue lined up to host us for a project.

One of our crew bought a decommissioned school bus from Idaho. We renovated the interior, fixed the obvious engine problems, and hit the road. We ended up with eight sponsors, 40 collaborating groups, 30 cities, and a two-month round trip. One person filmed professionally; the rest of us documented on our phones.

We called it the U.S. Bus Art Tour. The bus was named Knower – inspired a bit by Ken Kesey’s Furthur – and the tour became Know Going Back. The trip was loaded with ceramic stops, our clay sponsor stocked us with materials, and we decided to make plein-air clay landscapes instead of painted ones. We made it to Ohio (barely – the bus almost died), then down to Art Basel Miami, back up for the museum opening, through New York, and home to California via the South.

Since then we’ve done a couple of shorter tours, all filmed, and we’re now planning our biggest project yet – a 120-foot clay-and-paint mural at Oakland International Airport (OAK). We’re fundraising now. Projects like this are almost impossible for one artist alone, but with a group – and a traveling bus – it works.

We’ve just finished the teaser film for the first tour and will start pitching it to festivals soon. The dream is for it to become an ongoing TV series.

Any standout moments from the road that still stick with you?

So many. Painting the bus in front of the Axel Hotel on Collins Ave – the main drag in Miami Beach – during Art Basel Art Week. Showing our tour art at the Spectrum Art Fair in Wynwood, hosted by Topo Chico.

Building a 10-foot clay column with John Balistreri’s students at Bowling Green State University in Ohio – five different classes, six students per section, all stacked together in just four hours.

Visiting Mission Clay Arts and Industry in Arizona is always mind-blowing, but more than half our group had never been there, so seeing them experience it for the first time was unforgettable.

The Everson Museum in Syracuse, New York, hosted us right before Christmas, and we made clay projects with a lot of little kids. Near Kansas City, we worked with Englewood Arts Center and Belger Arts Center on a 50-foot anti-smoking mural, painted on recycled billboard vinyl for the front of their building.

At the Kaneko Arts Center in Omaha, Nebraska, we created multiple wall murals in their front gallery and spent time in community workshops. In Pennsylvania, we made a ceramic mural with the Greensburg Art Center, which they later installed after firing.

In Denver, La Serra Collective not only let us make large-scale ceramics at their studio-winery but also saved the trip by fixing our bus engine. They have an anagama kiln tunneled into the side of a mountain, and they fired our big clay piece the following summer.

One of the most moving moments was visiting the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., for the first major retrospective of Hung Liu’s work – just months after she had unexpectedly passed away. Hung was one of our art heroes, and documenting that show on film meant a lot.

There were so many moments like that – experiences that simply wouldn’t have happened without the context of the U.S. Bus Art Tour.

With Firehouse Films, you and Iris are telling stories through a different lens. What did making No Rules In Clay open up about the California ceramics scene – and have you thought about stepping in as host for future episodes?

Firehouse Films is our vehicle for stepping into movie and documentary production with the arts. The goal is to tell rich, exciting, and often overlooked stories about artists – projects that, for some reason, rarely make it to the screen. Iris is a fabulous producer and often brings us into major productions, sometimes under our individual names when appropriate. She got us on the production team for Everything Everywhere All At Once, which was a great example of where things can go.

By turning the lens on our visual art heroes, we see an opportunity to create something that’s both educational and entertaining. There’s a magic in combining artistic innovation with pure entertainment – a path not often taken in visual arts filmmaking.

Our feature documentary No Rules In Clay opened that door wide. We’ve been working on it for over eight years now, and the U.S. Bus Art Tour has become another way to meet and film artists – not just ceramicists, but creatives of all kinds.

Ceramics history often gets lost in the public eye because the fine art world has historically classified it as craft. Our story dives into how, in the late 1950s, a group of brave artists broke out of the mold of functional pottery and created wild, abstract sculpture. Their work paralleled the Abstract Expressionist movement in painting, and later gave rise to the playful, inventive sculpture of the Ceramic Funk Movement – one of the greatest yet least-known art movements in American history. We want to change that.

And yes – I’d be thrilled to step in as a host for future films or short episodes. It’s one of the most rewarding projects I’ve ever worked on. As an artist, it’s the ultimate gift to have a reason to visit our art heroes, hear in their own words, see inside their studios, about what they are doing.

“Projects like this are almost impossible for one artist alone, but with a group – and a traveling bus – it works.”

Are there other film ideas or projects on the horizon?

Yes – quite a few. We recently worked with the endlessly creative writer-director Boots Riley on his new film I Love Boosters, which should be out later this year.

Early next year, we have Ines coming out – a project with our Mexico City production team, Our Roots, led by writer-directors David Liles and Hugo Payen. The story follows a photographer documenting an extinct culture in Cabo San Lucas, who becomes entangled in a land marked by revolution, foreign exploitation, and a forbidden love that defies social, racial, and political boundaries.

We’re also close to greenlighting Ultra, which follows a young woman running the Badwater 135 Ultramarathon – considered “the world’s toughest foot race” – a 135-mile course through Death Valley in July, where temperatures can exceed 120°F (49°C), and where the hottest temperature ever recorded on Earth was 134.1°F.

I love collaborating with my wife, Iris Torres, on her film production adventures. She pulls me into the movies, and I pull her into the art projects.

Have large-scale ceramic murals entered your orbit yet – or do you see yourself moving in that direction? What shifts when ceramics go from object to environment?

One of our main ongoing sponsors is Laguna Clay Company – the world’s largest ceramic supply company, based just outside L.A. in the City of Industry. I was recently filming during their annual open house, LagunaPalooza, when the factory swaps the usual hum of machines for a huge crowd of visitors. They’re also deeply involved in community projects, and I’m often there filming day-to-day activities for a short documentary on “a day in the life.”

Our ceramic mural teams will be working with Laguna again, tackling both large-scale walls like the Oakland Airport OAK mural, and smaller projects, such as a 6’x6’ community clay mural at the Rossmoor Ceramic Arts Club in Orinda, California. I’ll be giving a lecture to their group, then using what would usually be my demo slot to make a mural with their members that celebrates their city.

Going from a sculptural object to an immersive environment is a big deal right now. You can see it in the success of groups like Meow Wolf and Burning Man – people crave these kinds of experiences. My goal as an artist is to encourage everyone to incorporate creative practice into daily life. Like exercise or a healthy diet, creativity is essential for mental, physical, and spiritual health – not just for artists, but for everyone. That starts with seeing life itself as an immersive art installation, where everything around you is material for your own creativity.

And to be more specific – ceramic murals are fun, energizing projects for communities because they’re rare. There’s a unique excitement when one happens.

What’s the best of Oakland right now?

For me, it’s the people. I’ve lived here for 21 years, and there’s a certain vibration in the air – a feeling of connection you can sense just walking down the street. I don’t even have to talk to anyone to feel it, though inevitably someone will say “what’s up” and start a conversation. That’s Oakland.

Know Going Back

From found objects to monumental clay pipes, Tom Franco moves between sculpture, storytelling, and community with ease. Splitting time between Oakland and LA, he builds big, plays loose, and treats every project as a chapter in an ever-evolving narrative that folds friends, places, and wild ideas into the mix.

You studied at both UCSC and CCA – two very different creative environments. How did each shape your instincts as an artist?

It’s an interesting comparison. Santa Cruz came first, and I already knew I wanted to study art and be an artist. My late, great first sculpting teacher, Bill Iaculla, gave me the visual example of a sculptor’s life, pre-college, and introduced me to the medium of found objects. That hooked me right away. Any time I saw pictures of active sculptor studios, I knew I spoke the language – which is why publications like this one are so important. I find sculptors can sometimes get lost in the weeds unnecessarily, which is a terrible thing to wish for going into this.

UCSC had a new welding department facility, and that’s where I ended up spending my favorite time – culminating in my senior year making larger-than-life metal imaginative creatures. That was back in 2002, and there was no graduate program at the time, so I floundered for another year before finding my way to Oakland, where I’ve been ever since. With my wife and baby, we now split time between Oakland and LA.

What California College of the Arts gave me was a community of people who had taken the leap to attend full-time art school, some great teachers like John Toki and Arthur Gonzalez, and my personal jump from metal into ceramics. I never seem to let a good medium go once the spark is lit – so even while making ceramic sculptures, I was using mixed media to scale up faster. The Oakland ceramic campus gave me a few beautiful gifts that still define my approach today – working collaboratively in the moment with other visual artists; finding a marriage between steel welding and clay, each acting as a perfect medium with its liquid form as the glue; and discovering the clay revolutionary movement of the late 1950s, later known as Funk Ceramics.

Art school was also where I first hatched the idea and desire to open my own community art studio venture – the Firehouse Art Collective. Sticking together allowed me to keep a studio after school, and my most consistent accomplishment as an artist has been taking over beautiful buildings and inviting artists to rent studio space. Without a physical location, nothing seems to stick. This has been going for 21 years now, across 10 different locations.

“I often weave ten works from a series into one narrative, pairing three to five influences to see what new story emerges.”

The large ceramic pipes came into your practice a few years back – what was it about that form and process that intrigued you?

Mission Clay Arts and Industry has been running for 49 years as a kind of alternative-style residency program with no real rules – other than, once in a while, throwing artists of any background into deep creative waters to see if they can swim. Off to the side of a huge industrial factory is an art studio, while the main floor pumps out eight-foot-tall sections of water pipes built to survive underground for city infrastructure.

These pipes have walls so thick I can barely make a C shape with my fingers over the lip, and they’re wide enough that I can’t wrap my arms around them. In the wet state, fresh from the three-story extruder and standing vertically, if one fell on someone, it could kill them. Punch the wet clay wall with full force, and you’d break your hand.

Making art with these forms was intimidating, to say the least. I brought four people with me to tackle making twelve pipes over about a year and a half, across three visits. The goal was a show at the Arizona State University Ceramics Research Center and Archive, and since then, we’ve installed them at various public venues around the Bay Area.

Working on something larger than life, on a huge chunk of ceramics, felt like graduating into a club very few people get to join. This kind of work isn’t done in isolation – it starts to feel like making a feature film or competing in high-level sports, where people’s best abilities come out.

I’ve become fascinated with what it takes for artists to work on this scale, especially without the extruded pipe form as a base. The 1950s ceramic revolution had a big branch of artists experimenting with immense, free-form ceramic sculptures – wild and unbound. The Mission Clay directors come directly from that lineage and are still pushing the boundaries of what’s possible in clay today.

And the pipe form itself is mesmerizing. It’s a shape that’s everywhere in daily life without us really noticing. Certain forms are the backbone of how we experience art – like the rectangular canvas for most paintings, or the ceramic cup every potter makes and reinvents, or even the invention of the wheel, or the concept of zero. Stretch that circular form into 3D, and you get the pipe – the shape we’re working with at the factory.

Are there any ceramic pieces or artists you keep returning to for inspiration? What is it about their work that speaks to you?

I’m a big believer in not copying, but paying homage to my favorite artists in my own work. Most of the time, I create out of pure enjoyment – the impulse to make something with my hands. If the work starts to feel boring, too predictable, or bound by expectations of how it’s “supposed” to look, I mentally reject it.

I love drawing alongside kids because the spontaneity is so high and the clarity of ideas is so sharp – though yes, there’s the cleanup factor. That goes for adults, too. Over the years, I’ve developed tricks to get into the creative zone depending on my mood.

Collecting found objects is my primary one. I imagine what they could become in a second or third life. Collaboration is another – returning again and again to my favorite artist peers, as if we’re in a band. I use mixed media to heighten the sculptural quality of the work, often with industrial epoxy. And whenever possible, I incorporate other artists’ work into mine. That began with anonymous pieces rescued from the trash, and evolved into using works by friends and known artists as part of my own narratives.

Sometimes I’ll depict an art hero making their own work – like my small ceramic scene of Viola Frey in her CCAC studio, surrounded by three of her 13-foot figures, done loosely in her style. Or painting Sister Gertrude Morgan’s imagery as miniature canvases on the walls of my own sculptures – her life with Jesus, angels, and community scenes, reinterpreted through my hand.

This past year I made a miniature clay portrait of Jackson Pollock wearing a full-sized motorcycle helmet, crossed with metal pieces on top, each capped with tiny beer bottles at the corners, with colorful strings running into his mouth – a playful nod to a beer-guzzler party hat. I did it because I love Jack’s work, and it gave me a way to spend more time with him. I’m drawn to innovators who push ideas in unexpected ways.

Because the work transforms so much in my hands, I’m never too concerned about “copying.” It’s about combining sources to create something entirely new. Each sculpture might carry three to five influences, and then I often weave ten or so finished works into a single storybook narrative. Working this way, a new visual story always emerges.

And I should mention my mentor, John Toki, who continually inspires me – not only through his monumental free-standing clay works, but also through his deep commitment to community building and service to other artists.

“As a little kid, my mom once let me spend my $2 allowance on some random plumbing hardware simply because it ‘looked cool.’”

Toys and found objects often show up in your work as playful characters. What draws you to them – and what do you love about telling stories that way?

Part of it is the joy of collecting. I once worried that, as an adult, I’d never again feel the thrill of buying a toy and playing with it like I did as a kid – until I realized I could incorporate all those things into sculptures. That wall just lifted, and suddenly everything was fair game again.

It works both ways, too. As a little kid, my mom once let me spend my $2 allowance on some random plumbing hardware simply because it “looked cool.”

The same goes for objects tied to habits I’ve since given up – like alcohol and smoking paraphernalia. For example, I’ve glued beer and liquor bottles into my work. I have a series of beer steins with narratives sculpted into the sides, each topped with a second beer bottle that continues the original story in paint.

As someone who studies vessel forms, I often fill them with sculptural shapes – whether built from my own cups or someone else’s finished pieces. I might take wet clay and build an upside-down cup, or what I call a “mountain form,” then tell a story in medium relief around the surface.

Much of this process circles back to storytelling – sometimes about my own life, sometimes about the objects themselves. My brain works like a detective searching for visual clues in an object, until fantasy takes over. I sometimes wonder if it’s all one long, ongoing story that I keep expanding with each new piece.

In many ways, I think that’s true. When I’m feeling particularly ambitious, I try to define the world these works are coming from. Maybe it’s half about unlocking my own psyche and consciousness, step by step, to get closer to being free.

You split your time between Oakland and Los Angeles – how does each city influence the way you work, think, or build community?

I grew up in Palo Alto, then moved to the East Bay and quickly realized most of the artists were there. Only through travel and hindsight do I see how unique that was. The arts community in Oakland and Berkeley has immersed me in an ongoing creative process – people are so generous, willing to go to any length to make their work, and I find that endlessly inspiring.

That said, I can’t just stay insulated in one place. Los Angeles is a massive, professional city that expands my horizons and connects me to a much broader network. The systems in LA are uniquely set up to reach the world – and to be accessible to everyone.

I love the exchange between the two. There’s a beauty in bringing the community spirit of the East Bay to LA – and then carrying the broader expertise back to the East Bay, reaching even more people.

“My brain works like a detective searching for visual clues in an object, until fantasy takes over.”

Alongside guitars, you’ve also used skateboards as canvases – how do these unexpected surfaces shape the stories you want to tell?

I’m not the first to paint on guitars or skateboards, but it’s still something you don’t see too often. Skateboard decks are made from the best, most durable plywood out there – if there were a way to access a full 4' x 8' sheet that would be crazy cool, but no one makes that, and it would be insanely expensive. In comparison, I often get skateboard decks for free.

Just painting on a flat deck isn’t usually enough for me to get into a creative zone. I like to sketch a story, cut the edges into a more three-dimensional shape, and then paint it in. That way I’m engaging my sculptural mind while painting.

I think artists tend to either think in 2D or 3D – and it shows in their work. Some sculptors never touch color, and some painters never touch form. I bounce between the two, but I have to prepare myself for each because they come from different moods and thought patterns.

Other surfaces I’ve worked with include handsaws, basketballs and soccer balls (inflated or deflated), chairs, shoes, bottles, cups, the human face, and the human form. The narratives that come out of these shapes are often – abstract self-portraits from the inside out, groups of people, kids, sports in action, artists making art, meditators learning meditation, and animals acting like people: frogs, dogs, aliens, snakes, rabbits, big cats, flowers. And sometimes animals acting like animals – birds, dolphins, turtles, alligators, horses.

Right now I’m working on a series of two-legged walking dinosaurs, each seven feet tall, made from a single road bike, strategically cut and welded back together as if they were dinosaur bones. Their triangular bodies have shelves built into them that hold buildings loosely formed by hand out of clay. The clay is a special cone 15 body that dries quickly, cracks all over, and still holds its form – I love it. Inside the buildings live small communities, visible through the windows, nurturing trees. These dinosaurs roam high above the earth in their own microcosm of dino-pod life, waiting to stumble upon another kind of community out there.

How did the Know Going Back tour come together? Where’d the bus come from, and how were the artists chosen?

In 2021, I was invited to show work at the Canton Museum in Ohio. They gave me my own room and needed everything finished in advance so they could plan and promote. The challenge? Getting the work from California to Ohio on a shoestring budget.

Usually, I’d arrive early and make the work on site, turning it into a kind of traveling residency. Since that wasn’t an option, I decided to drive the work myself. Friends started jumping on board, and as we mapped the route, we realized how many great art stops we could make along the way. It snowballed into a formal tour – eight to ten artists at different stops – and we called ourselves The Grateful 8 to 10. Every six hours, we had a venue lined up to host us for a project.

One of our crew bought a decommissioned school bus from Idaho. We renovated the interior, fixed the obvious engine problems, and hit the road. We ended up with eight sponsors, 40 collaborating groups, 30 cities, and a two-month round trip. One person filmed professionally; the rest of us documented on our phones.

We called it the U.S. Bus Art Tour. The bus was named Knower – inspired a bit by Ken Kesey’s Furthur – and the tour became Know Going Back. The trip was loaded with ceramic stops, our clay sponsor stocked us with materials, and we decided to make plein-air clay landscapes instead of painted ones. We made it to Ohio (barely – the bus almost died), then down to Art Basel Miami, back up for the museum opening, through New York, and home to California via the South.

Since then we’ve done a couple of shorter tours, all filmed, and we’re now planning our biggest project yet – a 120-foot clay-and-paint mural at Oakland International Airport (OAK). We’re fundraising now. Projects like this are almost impossible for one artist alone, but with a group – and a traveling bus – it works.

We’ve just finished the teaser film for the first tour and will start pitching it to festivals soon. The dream is for it to become an ongoing TV series.

Any standout moments from the road that still stick with you?

So many. Painting the bus in front of the Axel Hotel on Collins Ave – the main drag in Miami Beach – during Art Basel Art Week. Showing our tour art at the Spectrum Art Fair in Wynwood, hosted by Topo Chico.

Building a 10-foot clay column with John Balistreri’s students at Bowling Green State University in Ohio – five different classes, six students per section, all stacked together in just four hours.

Visiting Mission Clay Arts and Industry in Arizona is always mind-blowing, but more than half our group had never been there, so seeing them experience it for the first time was unforgettable.

The Everson Museum in Syracuse, New York, hosted us right before Christmas, and we made clay projects with a lot of little kids. Near Kansas City, we worked with Englewood Arts Center and Belger Arts Center on a 50-foot anti-smoking mural, painted on recycled billboard vinyl for the front of their building.

At the Kaneko Arts Center in Omaha, Nebraska, we created multiple wall murals in their front gallery and spent time in community workshops. In Pennsylvania, we made a ceramic mural with the Greensburg Art Center, which they later installed after firing.

In Denver, La Serra Collective not only let us make large-scale ceramics at their studio-winery but also saved the trip by fixing our bus engine. They have an anagama kiln tunneled into the side of a mountain, and they fired our big clay piece the following summer.

One of the most moving moments was visiting the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., for the first major retrospective of Hung Liu’s work – just months after she had unexpectedly passed away. Hung was one of our art heroes, and documenting that show on film meant a lot.

There were so many moments like that – experiences that simply wouldn’t have happened without the context of the U.S. Bus Art Tour.

With Firehouse Films, you and Iris are telling stories through a different lens. What did making No Rules In Clay open up about the California ceramics scene – and have you thought about stepping in as host for future episodes?

Firehouse Films is our vehicle for stepping into movie and documentary production with the arts. The goal is to tell rich, exciting, and often overlooked stories about artists – projects that, for some reason, rarely make it to the screen. Iris is a fabulous producer and often brings us into major productions, sometimes under our individual names when appropriate. She got us on the production team for Everything Everywhere All At Once, which was a great example of where things can go.

By turning the lens on our visual art heroes, we see an opportunity to create something that’s both educational and entertaining. There’s a magic in combining artistic innovation with pure entertainment – a path not often taken in visual arts filmmaking.

Our feature documentary No Rules In Clay opened that door wide. We’ve been working on it for over eight years now, and the U.S. Bus Art Tour has become another way to meet and film artists – not just ceramicists, but creatives of all kinds.

Ceramics history often gets lost in the public eye because the fine art world has historically classified it as craft. Our story dives into how, in the late 1950s, a group of brave artists broke out of the mold of functional pottery and created wild, abstract sculpture. Their work paralleled the Abstract Expressionist movement in painting, and later gave rise to the playful, inventive sculpture of the Ceramic Funk Movement – one of the greatest yet least-known art movements in American history. We want to change that.

And yes – I’d be thrilled to step in as a host for future films or short episodes. It’s one of the most rewarding projects I’ve ever worked on. As an artist, it’s the ultimate gift to have a reason to visit our art heroes, hear in their own words, see inside their studios, about what they are doing.

“Projects like this are almost impossible for one artist alone, but with a group – and a traveling bus – it works.”

Are there other film ideas or projects on the horizon?

Yes – quite a few. We recently worked with the endlessly creative writer-director Boots Riley on his new film I Love Boosters, which should be out later this year.

Early next year, we have Ines coming out – a project with our Mexico City production team, Our Roots, led by writer-directors David Liles and Hugo Payen. The story follows a photographer documenting an extinct culture in Cabo San Lucas, who becomes entangled in a land marked by revolution, foreign exploitation, and a forbidden love that defies social, racial, and political boundaries.

We’re also close to greenlighting Ultra, which follows a young woman running the Badwater 135 Ultramarathon – considered “the world’s toughest foot race” – a 135-mile course through Death Valley in July, where temperatures can exceed 120°F (49°C), and where the hottest temperature ever recorded on Earth was 134.1°F.

I love collaborating with my wife, Iris Torres, on her film production adventures. She pulls me into the movies, and I pull her into the art projects.

Have large-scale ceramic murals entered your orbit yet – or do you see yourself moving in that direction? What shifts when ceramics go from object to environment?

One of our main ongoing sponsors is Laguna Clay Company – the world’s largest ceramic supply company, based just outside L.A. in the City of Industry. I was recently filming during their annual open house, LagunaPalooza, when the factory swaps the usual hum of machines for a huge crowd of visitors. They’re also deeply involved in community projects, and I’m often there filming day-to-day activities for a short documentary on “a day in the life.”

Our ceramic mural teams will be working with Laguna again, tackling both large-scale walls like the Oakland Airport OAK mural, and smaller projects, such as a 6’x6’ community clay mural at the Rossmoor Ceramic Arts Club in Orinda, California. I’ll be giving a lecture to their group, then using what would usually be my demo slot to make a mural with their members that celebrates their city.

Going from a sculptural object to an immersive environment is a big deal right now. You can see it in the success of groups like Meow Wolf and Burning Man – people crave these kinds of experiences. My goal as an artist is to encourage everyone to incorporate creative practice into daily life. Like exercise or a healthy diet, creativity is essential for mental, physical, and spiritual health – not just for artists, but for everyone. That starts with seeing life itself as an immersive art installation, where everything around you is material for your own creativity.

And to be more specific – ceramic murals are fun, energizing projects for communities because they’re rare. There’s a unique excitement when one happens.

What’s the best of Oakland right now?

For me, it’s the people. I’ve lived here for 21 years, and there’s a certain vibration in the air – a feeling of connection you can sense just walking down the street. I don’t even have to talk to anyone to feel it, though inevitably someone will say “what’s up” and start a conversation. That’s Oakland.