Outlaw Logic

Raised on American myths, Matt McCormick navigates cowboy icons, fractured narratives, and everyday objects — chasing meaning across galleries, garments, and books, where art’s borders blur and personal history finds new form.

“The rodeo, the Western, the outlaw – these are familiar symbols that allow me to speak about larger, more abstract ideas: masculinity, freedom, failure, delusion.”

When were you first drawn to American iconography – specifically cowboys and the rodeo?

I try to focus on subjects I have a personal, lived relationship to. That’s evolved over time, but growing up in America, the imagery around me was always mythologized, especially the cowboy. It’s an exaggerated, almost cartoonish symbol, but it’s also deeply embedded in how the country sees itself. As a visual language, it’s immediate and overdetermined, which makes it fertile ground. The rodeo, the Western, the outlaw – these are familiar symbols that allow me to speak about larger, more abstract ideas: masculinity, freedom, failure, delusion. It was a natural place to begin, but it’s also something I’ve tried to move through, or complicate, over time.

Your previous show, Enter and Exit Through the Same Gate, at John Doe Gallery was a duo show with Brendan Lynch. How did that collaboration come about?

Brendan and I have known each other nearly twenty years. We’ve always had an active, sometimes volatile dialogue around art – what it is, how it works, what it’s for. Over time, that’s become a kind of daily exchange: ideas, images, arguments, alignments. Last year, Alfonso Gonzales Jr. suggested we make that conversation public. The show wasn’t about compromise or shared authorship; it was about proximity. Two practices with their own language, intersecting briefly in one space. It was less a collaboration than a snapshot of ongoing tension.

Now you’ve got a solo show in Paris at Galerie Enrico Navarra. What is this new body of work about? I heard there’s a series of paired images with a narrative that ends in the middle.

Each show feels more like a constructed narrative to me, though I try to leave it open-ended. This new work centers on that liminal space between childhood and adulthood – the moments where things begin to change, often without you realizing it. It’s a period defined by uncertainty, by firsts, by instinctive responses to an unknown future. Some people are forced into it too early; others evade it entirely. I was interested in that tension.

The structure of the show is intentionally fractured. There’s no clear resolution. Certain threads begin and then disappear. It’s meant to feel like memory – ambiguous, nonlinear, emotionally loaded. The mediums reflect that: painting, sculpture, video, photography – each carries a different kind of weight. The materials are there to fill in the gaps between what I can say and what I can’t.

You’ve said that accessibility is important to your work. How do you reconcile that with the exclusivity of the art world?

It’s a constant negotiation. The art market is structured around scarcity, around ideas of access and ownership. I understand that system, and I’m not interested in pretending it doesn’t exist. But I also believe in the importance of making work that people can actually engage with, regardless of whether they’re collectors or not.

That’s why I make books, prints, clothing – alternate points of entry. I don’t see those things as less serious or less valuable. They’re simply different formats for transmitting the same ideas. The goal is for the work to live in more than one space at a time, and to speak to more than one kind of viewer.

Your apparel brand, One of These Days, feels like a natural extension of your visual practice. How did it begin, and where is it going?

I started it with Jered Vargas about ten years ago. It began informally, as a side project – an outlet for ideas that didn’t quite fit into the framework of a studio practice. Over time, it’s become something more structured and autonomous. When Mikol Brinkman came on board, it gave the brand the infrastructure it needed to scale without losing its core sensibility.

At this point, I see it as a long-term platform – one that can evolve with or without me. It’s a way of engaging with visual language and storytelling through a different set of tools, but it’s all part of the same larger impulse.

“Not everyone walks into a gallery. Some people walk into a bar. Some people buy a T-shirt, or a bottle of whiskey, or a record. Those are all valid ways of encountering an idea – of feeling something.”

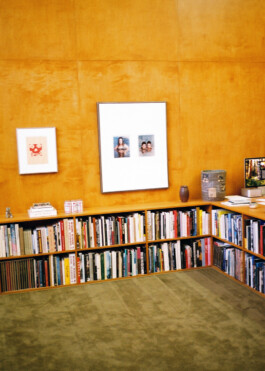

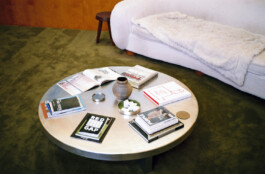

Highway Liaison, your publishing imprint, also feels deeply embedded in your practice. What led to its creation?

Books have always been essential to how I think and work. They’re a way of slowing down, of creating a fixed record in a world that moves quickly. Highway started from that – an interest in bookmaking as both a personal and collaborative act.

I also wanted to create a structure that could support other artists, whether that meant helping them realize a book, an edition, or something in between. The goal isn’t scale; it’s quality. I want each object to feel considered, intentional, and enduring. Books are democratic in a way most other art objects aren’t. That matters to me.

You’ve worked across a wide range of commercial and cultural spaces – bars, music, fragrance, apparel. What draws you to these forms of collaboration?

I’m interested in how ideas travel. Not everyone walks into a gallery. Some people walk into a bar. Some people buy a T-shirt, or a bottle of whiskey, or a record. Those are all valid ways of encountering an idea – of feeling something.

Artists like Warhol understood that – how culture is a system of images and objects, and how meaning is shaped by distribution. By seamlessly navigating between his traditional practice of drawing, painting, sculpture, video, photos, etc., and projects like managing The Velvet Underground or starting Interview Magazine, he essentially kicked open the door of what it meant to make art, especially in a manner that reaches the masses. I don’t think making something commercially viable means it has to lose its depth. If anything, it’s a challenge: how do you embed meaning into something that moves through a different circuit?

Each project is an extension of the same larger project – finding new ways to tell a story, or transmit a feeling, in the time and culture I’m living in.

“Books are democratic in a way most other art objects aren’t. That matters to me.”

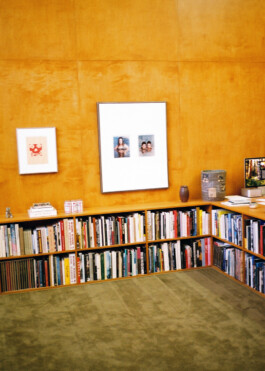

You’re an avid book collector. What are five volumes that have real personal value to you right now?

In no particular order:

All the books I’ve made – because I made them for a reason, and I wanted to live with them.

My childhood copy of The Phantom Tollbooth.

A book of my dad’s paintings – self-published by my parents, which taught me I could do the same.

Timothy Leary’s Chaos and Cyber Culture, inscribed to Aldous Huxley’s wife, Laura – a strange artifact that feels eerily relevant.

Martin Kippenberger’s The Canary Searching for a Port in the Storm. It came with a drawing, so it feels singular. But more than that, it’s one of the best examples of how a book can function as a complete artwork.

Outlaw Logic

Raised on American myths, Matt McCormick navigates cowboy icons, fractured narratives, and everyday objects — chasing meaning across galleries, garments, and books, where art’s borders blur and personal history finds new form.

“The rodeo, the Western, the outlaw – these are familiar symbols that allow me to speak about larger, more abstract ideas: masculinity, freedom, failure, delusion.”

When were you first drawn to American iconography – specifically cowboys and the rodeo?

I try to focus on subjects I have a personal, lived relationship to. That’s evolved over time, but growing up in America, the imagery around me was always mythologized, especially the cowboy. It’s an exaggerated, almost cartoonish symbol, but it’s also deeply embedded in how the country sees itself. As a visual language, it’s immediate and overdetermined, which makes it fertile ground. The rodeo, the Western, the outlaw – these are familiar symbols that allow me to speak about larger, more abstract ideas: masculinity, freedom, failure, delusion. It was a natural place to begin, but it’s also something I’ve tried to move through, or complicate, over time.

Your previous show, Enter and Exit Through the Same Gate, at John Doe Gallery was a duo show with Brendan Lynch. How did that collaboration come about?

Brendan and I have known each other nearly twenty years. We’ve always had an active, sometimes volatile dialogue around art – what it is, how it works, what it’s for. Over time, that’s become a kind of daily exchange: ideas, images, arguments, alignments. Last year, Alfonso Gonzales Jr. suggested we make that conversation public. The show wasn’t about compromise or shared authorship; it was about proximity. Two practices with their own language, intersecting briefly in one space. It was less a collaboration than a snapshot of ongoing tension.

Now you’ve got a solo show in Paris at Galerie Enrico Navarra. What is this new body of work about? I heard there’s a series of paired images with a narrative that ends in the middle.

Each show feels more like a constructed narrative to me, though I try to leave it open-ended. This new work centers on that liminal space between childhood and adulthood – the moments where things begin to change, often without you realizing it. It’s a period defined by uncertainty, by firsts, by instinctive responses to an unknown future. Some people are forced into it too early; others evade it entirely. I was interested in that tension.

The structure of the show is intentionally fractured. There’s no clear resolution. Certain threads begin and then disappear. It’s meant to feel like memory – ambiguous, nonlinear, emotionally loaded. The mediums reflect that: painting, sculpture, video, photography – each carries a different kind of weight. The materials are there to fill in the gaps between what I can say and what I can’t.

You’ve said that accessibility is important to your work. How do you reconcile that with the exclusivity of the art world?

It’s a constant negotiation. The art market is structured around scarcity, around ideas of access and ownership. I understand that system, and I’m not interested in pretending it doesn’t exist. But I also believe in the importance of making work that people can actually engage with, regardless of whether they’re collectors or not.

That’s why I make books, prints, clothing – alternate points of entry. I don’t see those things as less serious or less valuable. They’re simply different formats for transmitting the same ideas. The goal is for the work to live in more than one space at a time, and to speak to more than one kind of viewer.

Your apparel brand, One of These Days, feels like a natural extension of your visual practice. How did it begin, and where is it going?

I started it with Jered Vargas about ten years ago. It began informally, as a side project – an outlet for ideas that didn’t quite fit into the framework of a studio practice. Over time, it’s become something more structured and autonomous. When Mikol Brinkman came on board, it gave the brand the infrastructure it needed to scale without losing its core sensibility.

At this point, I see it as a long-term platform – one that can evolve with or without me. It’s a way of engaging with visual language and storytelling through a different set of tools, but it’s all part of the same larger impulse.

“Not everyone walks into a gallery. Some people walk into a bar. Some people buy a T-shirt, or a bottle of whiskey, or a record. Those are all valid ways of encountering an idea – of feeling something.”

Highway Liaison, your publishing imprint, also feels deeply embedded in your practice. What led to its creation?

Books have always been essential to how I think and work. They’re a way of slowing down, of creating a fixed record in a world that moves quickly. Highway started from that – an interest in bookmaking as both a personal and collaborative act.

I also wanted to create a structure that could support other artists, whether that meant helping them realize a book, an edition, or something in between. The goal isn’t scale; it’s quality. I want each object to feel considered, intentional, and enduring. Books are democratic in a way most other art objects aren’t. That matters to me.

You’ve worked across a wide range of commercial and cultural spaces – bars, music, fragrance, apparel. What draws you to these forms of collaboration?

I’m interested in how ideas travel. Not everyone walks into a gallery. Some people walk into a bar. Some people buy a T-shirt, or a bottle of whiskey, or a record. Those are all valid ways of encountering an idea – of feeling something.

Artists like Warhol understood that – how culture is a system of images and objects, and how meaning is shaped by distribution. By seamlessly navigating between his traditional practice of drawing, painting, sculpture, video, photos, etc., and projects like managing The Velvet Underground or starting Interview Magazine, he essentially kicked open the door of what it meant to make art, especially in a manner that reaches the masses. I don’t think making something commercially viable means it has to lose its depth. If anything, it’s a challenge: how do you embed meaning into something that moves through a different circuit?

Each project is an extension of the same larger project – finding new ways to tell a story, or transmit a feeling, in the time and culture I’m living in.

“Books are democratic in a way most other art objects aren’t. That matters to me.”

You’re an avid book collector. What are five volumes that have real personal value to you right now?

In no particular order:

All the books I’ve made – because I made them for a reason, and I wanted to live with them.

My childhood copy of The Phantom Tollbooth.

A book of my dad’s paintings – self-published by my parents, which taught me I could do the same.

Timothy Leary’s Chaos and Cyber Culture, inscribed to Aldous Huxley’s wife, Laura – a strange artifact that feels eerily relevant.

Martin Kippenberger’s The Canary Searching for a Port in the Storm. It came with a drawing, so it feels singular. But more than that, it’s one of the best examples of how a book can function as a complete artwork.