Natural Order

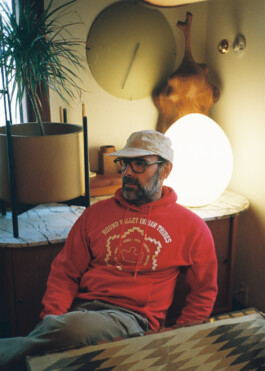

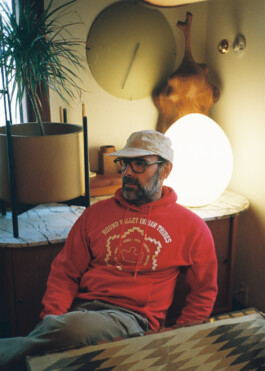

Mason St. Peter builds spaces the way he lives – with clarity, curiosity, and a quiet respect for the things that shape us. Skateboards, sound systems, Navajo rugs, jazz records, California light… it all folds in. A life assembled with intention, one material and one moment at a time.

When did it first dawn on you that architecture could be a real career path?

I started architecture school around ’98… by the time I graduated I was convinced that architecture might not be the path anymore. While I was studying, I worked in different offices – for some of my instructors, big firms, boutique studios – lots of different egos and experiences of what it’s like to be an architect, and at that point I wasn’t feeling any connection.

I don’t know what the percentage is, but lots of people who go to architecture school end up never even practicing… the saying is that training to become an architect gives you the tools and skills to become anything else: sociologist, psychologist, archaeologist, historian, political scientist, artist, photographer, philosopher, etc.

I was also one of those who participated in the graduation ceremony even though I still had two more classes to complete. Three years later, I went back and completed the rest of the requirements for my degree. So I guess the confidence came later, but it wasn’t until after I had opened two side businesses that I thought, maybe architecture could be a career, and founded my own firm.

What were the biggest takeaways from your time at California College of the Arts, and did you transition straight into an architectural practice afterward?

When I started, it was California College of Arts and Crafts (CCAC), and just before I graduated they dropped the “Crafts”… right on the heels of the California Craft Movement (I would later open a store dedicated to craft).

Studying architecture at CCA was a mind-altering experience. Every day felt like another adventure into endless opportunity and exploration. The way the school was arranged, you could browse a graphic design critique, see how your friend’s wood-furniture project was evolving, take in a fashion show, sit in on an industrial design forum, attend a fine art symposium, or check out the lecture series.

When I was at CCA, I felt like I was in the right place – understood, nurtured, becoming something.

When I graduated, I didn’t directly pursue architecture, however. I was sidetracked by addiction; I went to rehab (21 years sober now). For that first six months afterward, I wasn’t quite sure how to move forward. I did some design-build consulting with a friend, then took a job at a mid-sized firm that specialized in residential-over-retail projects. My marriage didn’t seem to make sense anymore (I started therapy for the first time), so there were transitions that needed to happen before I eventually ended up working for a boutique firm that specialized in Eichler restoration.

It took about five years for me to start my own firm.

“I wanted my own style long before I knew what style even was.”

You’ve cited Schindler and Neutra as early influences. What part of their thinking still guides you – and where have you carved out your own path?

I always admired how they came to California from Europe to work for Frank Lloyd Wright, but ended up becoming the godfathers of California modernism. Their approach to design feels to me like: we’re going to do everything, but in such a way that it looks like we’re doing nothing.

The level of detail in all of Neutra’s projects is insane – the way he used the affordable materials of the time with the highest level of design, integrating them seamlessly… mind-blowing.

Schindler and his use of plywood for everything – built-ins, finish material, custom furniture – was an early inspiration because it connected to my childhood experiences building wood ramps and half pipes for skateboarding.

How does the idea of indoor–outdoor living shape your work – especially designing along the West Coast?

It’s everything. Growing up in Southern California in the late ’70s through the ’90s, all we ever did was play outside (I’m a Gen X kid). When I’m at the beach or in the mountains or the canyons, I’m often saying to myself, “Wouldn’t it be nice if this was a house?”

Being outside is just as important – if not more important – than being inside. Especially now with kids, the connection to nature, to the outside world, to being in the elements feels more important than ever… you know, with technology and screens and all that.

Tell me about the adventure of opening General Store – what sparked it, and what did you learn from that chapter?

Opening General Store was huge. It taught me so many life lessons – how to run a business, how not to run a business, what it means to have a life philosophy or ethos you try to implement.

It was the end of 2009 and the recession was in full effect. Nobody thought it was a good idea. It wasn’t originally intended to be successful – there were backup plans for how to use the space if the store failed – and I was young, idealistic, clear-headed, full of ambition. From the beginning you could say it was more of a passion project: the way the store was designed, the use of plywood everywhere, the portal (an inverted half-pipe/full-pipe), the forced perspective created by angling the walls. Many of the design principles I learned in architecture school were implemented – ideas that are sometimes difficult to get a client to agree to.

The store gave me the confidence to start my own practice. The relationships and experiences I developed by putting myself out there – taking that chance – are lifelong and invaluable.

“Being outside is just as important – if not more – than being inside.”

You also do custom builds and furniture – how does that hands-on work inform your architectural approach?

In the past, I’ve built small structures and custom furniture for myself or clients, and over the years I’ve realized I’m much better on the design side than the build side. It takes a lot of patience and skill to be a craftsperson. I do okay, but folks who do it as their passion are much more equipped than I am – and I know my lane. So I try to stay in it.

When did you start collecting skateboards, and what does the collection represent for you now – is there one board with a particularly wild story behind it?

I started early – maybe in my teens. I had built a ramp in my garage for rainy days. This was back in the era of no skateparks, so having your own place to skate was pretty bitchin’. The old decks I had were nailed onto the walls as decoration, so I guess it began there.

Later, after I got sober, I started skating again more seriously. In my early 30s I was at the height of my personal skating abilities. That’s when I started seeking out the boards I had when I was a teen, and the collection turned more serious. For the next 10 years or so, I was able to put together a collection of the boards I had ridden that meant something to me – and now I’m beginning to feel like I could let it go. It has served its purpose. Like many collections, it filled a void, and that void no longer exists.

You also collect Navajo rugs and vinyl records – what draws you to objects with history and handwork, and how do they live alongside your own design sensibility?

Records have been a big part of my life from early on. I’ve always had a huge connection to music. Each record is like a book – they tell a story. Liner notes, album artwork, locked grooves, etchings… there’s a lot that goes into it: graphic design, interpretation, storytelling. I can see a lot of parallels to architecture.

Collecting Navajo rugs has been more of a cultural connection for me. We are Wailaki, Nomalaki, and Concow. Having the physical patterns and functional fabric come together in the weaving is highly sensory, evocative, and of course very spiritual.

You’re really into sound and have multiple systems at home – including the one your brother built that can get seriously loud. What does great sound do for you, and how does it shape the atmosphere you want to live in?

I’ve definitely developed an appreciation for antiquated audio – tube and solid-state – something where you can see the individual elements functioning together to create sound. It’s very intriguing. However, most anything these days will work to share the one thing that’s most important: the music.

These days I mostly play records so I can have a little dance party with my family or take my mind off the stresses of the moment.

“You could probably surf a 2×4 with a nail for a fin if you’re patient enough.”

I heard you once scored a great deal on a collection of jazz records – what’s the story there, and do you remember the first one you put on?

My older brother got me into jazz in my youth. He studied it. I also remember jazz in skate videos – I connected with the way it felt freeform but still structured.

Recently, I started a project for a client who had a large vinyl collection in storage for many years, and we agreed to a trade. The albums hadn’t been touched in maybe 25 years – each one in perfect, meticulously cared-for condition. I started with Horace Silver, and I still haven’t gotten through all of them.

Your surfboards are all by Marc Andreini – what keeps you coming back to him specifically?

I know him, and I respect his story – his life choices. He’s someone who has wrestled with the way society might perceive the validity or legitimacy of your passion. I felt that way as a youth with skateboarding. He also had some similar patriarchal, self-imposed pressures he may have felt obligated to uphold, which I understood. And he’s just an all-around great guy.

Being good at surfing is a skill like most things – it’s the person who controls the object, not the other way around. You could probably surf a 2×4 with a nail for a fin if you’re patient and persistent. But we can all see and appreciate greatness in design. Marc is a master of his craft. His designs have a feeling that’s personal to me, and I connect to them.

How would you describe your own sense of style – is it something you consciously shape, or something that naturally forms around you?

Evolving. From an early age, I felt the desire not to be like other people. That sounds self-aggrandizing now, but I think it’s accurate. I wanted my own style. I think it’s why for the longest time I never had any heroes.

I’m pretty anti-sports – don’t get me wrong, I love going to a game and being in a stadium – but the way sports can corrupt athletes is disturbing to me.

In the past, my personal style leaned heavily toward vintage. Over the past five years or so, I’ve thinned out my closet… less an athlete, more part of the team. I’ve found some contemporary designers and brands that feel like me, and I’ve embraced new in a way that feels right now.

If you had zero constraints on your next project – budget, code, location – what would you design, and why?

A beach house, on the beach at First Point, Malibu, for my family and me.

Natural Order

Mason St. Peter builds spaces the way he lives – with clarity, curiosity, and a quiet respect for the things that shape us. Skateboards, sound systems, Navajo rugs, jazz records, California light… it all folds in. A life assembled with intention, one material and one moment at a time.

When did it first dawn on you that architecture could be a real career path?

I started architecture school around ’98… by the time I graduated I was convinced that architecture might not be the path anymore. While I was studying, I worked in different offices – for some of my instructors, big firms, boutique studios – lots of different egos and experiences of what it’s like to be an architect, and at that point I wasn’t feeling any connection.

I don’t know what the percentage is, but lots of people who go to architecture school end up never even practicing… the saying is that training to become an architect gives you the tools and skills to become anything else: sociologist, psychologist, archaeologist, historian, political scientist, artist, photographer, philosopher, etc.

I was also one of those who participated in the graduation ceremony even though I still had two more classes to complete. Three years later, I went back and completed the rest of the requirements for my degree. So I guess the confidence came later, but it wasn’t until after I had opened two side businesses that I thought, maybe architecture could be a career, and founded my own firm.

What were the biggest takeaways from your time at California College of the Arts, and did you transition straight into an architectural practice afterward?

When I started, it was California College of Arts and Crafts (CCAC), and just before I graduated they dropped the “Crafts”… right on the heels of the California Craft Movement (I would later open a store dedicated to craft).

Studying architecture at CCA was a mind-altering experience. Every day felt like another adventure into endless opportunity and exploration. The way the school was arranged, you could browse a graphic design critique, see how your friend’s wood-furniture project was evolving, take in a fashion show, sit in on an industrial design forum, attend a fine art symposium, or check out the lecture series.

When I was at CCA, I felt like I was in the right place – understood, nurtured, becoming something.

When I graduated, I didn’t directly pursue architecture, however. I was sidetracked by addiction; I went to rehab (21 years sober now). For that first six months afterward, I wasn’t quite sure how to move forward. I did some design-build consulting with a friend, then took a job at a mid-sized firm that specialized in residential-over-retail projects. My marriage didn’t seem to make sense anymore (I started therapy for the first time), so there were transitions that needed to happen before I eventually ended up working for a boutique firm that specialized in Eichler restoration.

It took about five years for me to start my own firm.

“I wanted my own style long before I knew what style even was.”

You’ve cited Schindler and Neutra as early influences. What part of their thinking still guides you – and where have you carved out your own path?

I always admired how they came to California from Europe to work for Frank Lloyd Wright, but ended up becoming the godfathers of California modernism. Their approach to design feels to me like: we’re going to do everything, but in such a way that it looks like we’re doing nothing.

The level of detail in all of Neutra’s projects is insane – the way he used the affordable materials of the time with the highest level of design, integrating them seamlessly… mind-blowing.

Schindler and his use of plywood for everything – built-ins, finish material, custom furniture – was an early inspiration because it connected to my childhood experiences building wood ramps and half pipes for skateboarding.

How does the idea of indoor–outdoor living shape your work – especially designing along the West Coast?

It’s everything. Growing up in Southern California in the late ’70s through the ’90s, all we ever did was play outside (I’m a Gen X kid). When I’m at the beach or in the mountains or the canyons, I’m often saying to myself, “Wouldn’t it be nice if this was a house?”

Being outside is just as important – if not more important – than being inside. Especially now with kids, the connection to nature, to the outside world, to being in the elements feels more important than ever… you know, with technology and screens and all that.

Tell me about the adventure of opening General Store – what sparked it, and what did you learn from that chapter?

Opening General Store was huge. It taught me so many life lessons – how to run a business, how not to run a business, what it means to have a life philosophy or ethos you try to implement.

It was the end of 2009 and the recession was in full effect. Nobody thought it was a good idea. It wasn’t originally intended to be successful – there were backup plans for how to use the space if the store failed – and I was young, idealistic, clear-headed, full of ambition. From the beginning you could say it was more of a passion project: the way the store was designed, the use of plywood everywhere, the portal (an inverted half-pipe/full-pipe), the forced perspective created by angling the walls. Many of the design principles I learned in architecture school were implemented – ideas that are sometimes difficult to get a client to agree to.

The store gave me the confidence to start my own practice. The relationships and experiences I developed by putting myself out there – taking that chance – are lifelong and invaluable.

“Being outside is just as important – if not more – than being inside.”

You also do custom builds and furniture – how does that hands-on work inform your architectural approach?

In the past, I’ve built small structures and custom furniture for myself or clients, and over the years I’ve realized I’m much better on the design side than the build side. It takes a lot of patience and skill to be a craftsperson. I do okay, but folks who do it as their passion are much more equipped than I am – and I know my lane. So I try to stay in it.

When did you start collecting skateboards, and what does the collection represent for you now – is there one board with a particularly wild story behind it?

I started early – maybe in my teens. I had built a ramp in my garage for rainy days. This was back in the era of no skateparks, so having your own place to skate was pretty bitchin’. The old decks I had were nailed onto the walls as decoration, so I guess it began there.

Later, after I got sober, I started skating again more seriously. In my early 30s I was at the height of my personal skating abilities. That’s when I started seeking out the boards I had when I was a teen, and the collection turned more serious. For the next 10 years or so, I was able to put together a collection of the boards I had ridden that meant something to me – and now I’m beginning to feel like I could let it go. It has served its purpose. Like many collections, it filled a void, and that void no longer exists.

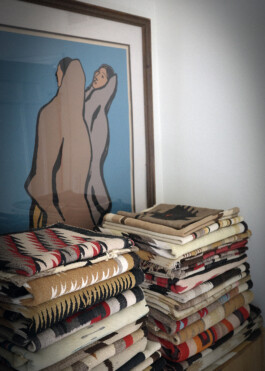

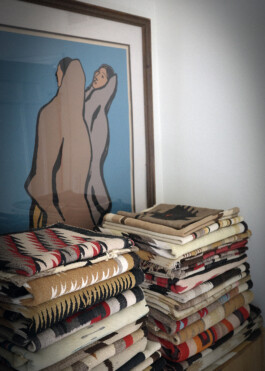

You also collect Navajo rugs and vinyl records – what draws you to objects with history and handwork, and how do they live alongside your own design sensibility?

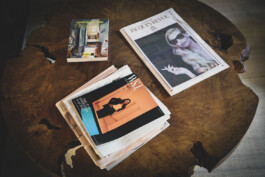

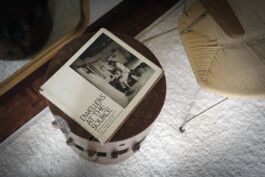

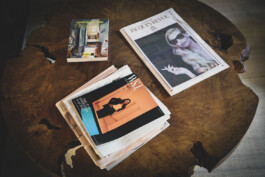

Records have been a big part of my life from early on. I’ve always had a huge connection to music. Each record is like a book – they tell a story. Liner notes, album artwork, locked grooves, etchings… there’s a lot that goes into it: graphic design, interpretation, storytelling. I can see a lot of parallels to architecture.

Collecting Navajo rugs has been more of a cultural connection for me. We are Wailaki, Nomalaki, and Concow. Having the physical patterns and functional fabric come together in the weaving is highly sensory, evocative, and of course very spiritual.

You’re really into sound and have multiple systems at home – including the one your brother built that can get seriously loud. What does great sound do for you, and how does it shape the atmosphere you want to live in?

I’ve definitely developed an appreciation for antiquated audio – tube and solid-state – something where you can see the individual elements functioning together to create sound. It’s very intriguing. However, most anything these days will work to share the one thing that’s most important: the music.

These days I mostly play records so I can have a little dance party with my family or take my mind off the stresses of the moment.

“You could probably surf a 2×4 with a nail for a fin if you’re patient enough.”

I heard you once scored a great deal on a collection of jazz records – what’s the story there, and do you remember the first one you put on?

My older brother got me into jazz in my youth. He studied it. I also remember jazz in skate videos – I connected with the way it felt freeform but still structured.

Recently, I started a project for a client who had a large vinyl collection in storage for many years, and we agreed to a trade. The albums hadn’t been touched in maybe 25 years – each one in perfect, meticulously cared-for condition. I started with Horace Silver, and I still haven’t gotten through all of them.

Your surfboards are all by Marc Andreini – what keeps you coming back to him specifically?

I know him, and I respect his story – his life choices. He’s someone who has wrestled with the way society might perceive the validity or legitimacy of your passion. I felt that way as a youth with skateboarding. He also had some similar patriarchal, self-imposed pressures he may have felt obligated to uphold, which I understood. And he’s just an all-around great guy.

Being good at surfing is a skill like most things – it’s the person who controls the object, not the other way around. You could probably surf a 2×4 with a nail for a fin if you’re patient and persistent. But we can all see and appreciate greatness in design. Marc is a master of his craft. His designs have a feeling that’s personal to me, and I connect to them.

How would you describe your own sense of style – is it something you consciously shape, or something that naturally forms around you?

Evolving. From an early age, I felt the desire not to be like other people. That sounds self-aggrandizing now, but I think it’s accurate. I wanted my own style. I think it’s why for the longest time I never had any heroes.

I’m pretty anti-sports – don’t get me wrong, I love going to a game and being in a stadium – but the way sports can corrupt athletes is disturbing to me.

In the past, my personal style leaned heavily toward vintage. Over the past five years or so, I’ve thinned out my closet… less an athlete, more part of the team. I’ve found some contemporary designers and brands that feel like me, and I’ve embraced new in a way that feels right now.

If you had zero constraints on your next project – budget, code, location – what would you design, and why?

A beach house, on the beach at First Point, Malibu, for my family and me.