Spiritual Leader

Sardines, tulips, paint pallets, and Disco’s eighth-note. These are the Spiritual Objects of Los Angeles based designer and artist Luc Fuller. A Pacific Northwest transplant, he’s approaching design through a new lens of parenting, though his work has always been whimsical.

Fuller’s design path has been an uninterrupted stream of adventure. Whether reclined in his old Jeep listening to John Coltrane as a teenager, meeting new design friends in questionable attire (more on that later), or learning his commissioned Tulip Table (that seats ten) provided a dance floor for an afterparty, there is an improvisational thread in his work.

A thread that not only blurs the line between artful and functional objects, but transcends it, like A Love Supreme. Coltrane’s “through-composed” album and Fuller’s creative work share a continuous, non-sectional, and non-repetitive nature, making myth of the everyday.

You grew up in the Pacific North West? Tell us about family life and growing up there.

When I think about growing up in the Northwest I think about being outside: riding bikes, swimming, camping, fishing, and spending time in the mountains. Coming from a large family (my dad is one of seven), I spent a lot of time with my cousins, aunts, and uncles. Interestingly, my parents actually grew up in Southern California but moved north after college. Eventually, all of my aunts, uncles, and grandparents followed suit and moved to Washington State, while I somehow ended up back in LA.

Were you drawn to art and design in your teenage years or did that come a bit later? What music, books or films stand out from this period?

I was definitely an art kid. Although I tried my hand at various sports, once I started playing music and taking art classes in middle school, everything else took a backseat. Without those art classes, I doubt I would have graduated high school.

It wasn’t until college that I had the opportunity to visit my first art museum beyond the small regional museum in Spokane. The lack of an immediately accessible visual culture in my hometown led to an unquenchable curiosity within me, which I still feel today.

Discovering something for the first time whether it’s from a hundred years ago, or yesterday, is a high that I’m constantly trying to get back to. I vividly remember the first time I listened to John Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme” in high school. My friend Ian insisted that we skip class and listen to it uninterrupted. We were sitting in my old Jeep with reclined seats, at a nearby park.

How did your work develop at Pacific Northwest College of Art and did you form a studio practice straight after?

PNCA was an excellent school. The undergraduate program resembled an MFA program, where our final year involved working with a mentor and developing a thesis that we had to defend. Interestingly, this academic approach to art and creativity contrasts with my current view of my practice. After graduating, I felt a strong sense of guilt for simply wanting to create things for the sake of creating. I think I’m just now getting to a place feeling comfortable in my own skin and not feeling any sense of shame or pressure to do anything other than go about things my own way.

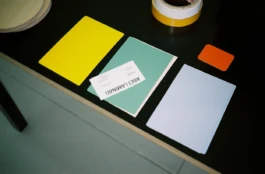

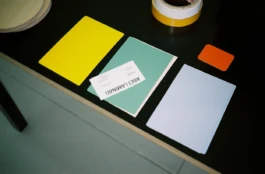

Your work around this time was primarily focused around paint, inkjet prints, and photographs. What other processes were you exploring then?

My work was all over the place! Looking back, I see that I was gradually pushing the boundaries of “painting” and “art,” exploring adjacent cultural realms such as fashion, music, and later, design. I can’t say it was the most interesting work on the planet, but it was a start.

“Three of my heroes—Franz West, Donald Judd, and Mary Heilmann—have all explored making functional objects in addition to their artistic pursuits.”

When did you transition into making objects and when was ‘Spiritual Objects’ born? Is the model rooted in this idea of ‘Everyday Objects?’

I believe the seed was planted while my wife and I were living in Copenhagen between 2015 and 2016. Design in Denmark, as well as many other parts of Europe, seamlessly integrates into everyday life. I found myself leaving museums equally inspired by the furniture, lighting, and architecture as I was by the art.

Moreover, many of my favorite artists have, at some point, created useful and functional objects, which always fascinated me. Three of my heroes—Franz West, Donald Judd, and Mary Heilmann—have all explored making functional objects in addition to their artistic pursuits.

In my perspective, the integration of functional objects into the realm of art blurs boundaries, resulting in art somehow becoming more accessible and human. Simultaneously, this fusion allows furniture and objects to surpass their mere practical utility and offer something deeper or more meaningful as well.

For me, getting into design was a gradual process. I kept it a secret for a couple of years while taking furniture design night classes at Art Center in Pasadena and setting up a small workshop in our garage.

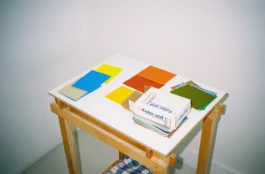

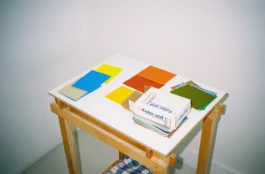

I officially launched Spiritual Objects in the fall of 2019 with a small collection that included the Disco Stool, the Sardine, and the Cutting Board. My goal was to create a platform that would grant me autonomy from the gallery world and allow me to create things I felt genuinely excited about, regardless of fitting neatly into a specific category.

Today, after nearly four years, Spiritual Objects operates as a design studio, an art practice, and a brand. Our projects encompass product design, furniture design, custom commissions, illustration, and occasional exhibitions.

“The after-party got completely out of hand and I learned the next morning that people were dancing on some of the tables, including mine.”

In recent years, are there any favorite pieces or notable commissions you’ve created that stand out?

I don’t have any particular favorites per se. For me, the connection to my work lies in what each product or project teaches me. With every new creation, new challenges arise, and I discover my preferences and dislikes regarding processes, materials, and approaches.

Last summer, I had the opportunity to design a large sculptural table for Copenhagen’s annual design festival, 3daysofdesign. Five designers/studios from five different countries were commissioned, with the only requirement being its functionality and ability to seat ten guests for a dinner party.

The whole project was an absolute blast, and eating dinner on my giant tulip-shaped table, sitting directly across from Carin Panton von Halem (designer Verner Panton’s daughter) is an experience I’ll never forget!

In typical Copenhagen fashion, the after-party got completely out of hand and I learned the next morning that people were dancing on some of the tables, including mine. To be honest, I don’t know what more I could have asked for.

You’re also developing a new project that is looking to fill a gap in the kids furniture market. Can you shed some light on this new venture?

I’m sure I’m not the first designer to have kids and suddenly want to start designing kids’ products, but it’s something that I couldn’t help exploring being both inspired by spending time with my son and disappointed by the lack of interesting products on the market. It’s still early days but the process has been quite fun, and I think natural for me as my work already has a playful simplicity embedded in everything I make. The project is also another excuse to work with other creatives, and eventually work with other designers as well to develop products.

“I recently tracked down Enzo Mari’s catalog from his recent show curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist in Milan.”

We can’t wait to see what you produce. Shifting to travel, as you’re the adventurous type, you had a pretty interesting exhibition in London, where we share mutual friends, right?

That first trip to London where I met our mutual friend Nick Bell changed my life.

I was there for about 5 weeks, painting, and preparing for my first proper solo exhibition at Rod Barton in Peckham. The gallery put me up at a nearby shared Airbnb, which happened to be Nick’s flat. I remember arriving in London really late and Nick and his flatmates left me a key because they were out partying.

When I woke up and went downstairs I saw Nick and one of his friends out in the garden, still up from the night before, half-naked in a fur coat, in full makeup. While still slightly under the influence of who knows what, he welcomed me as if we were family and proceeded to make me one of the worst coffees I’d ever had in my life. We’ve been best friends ever since!

That’s a vivid scene. What’s caught your curious eye as of late?

I think because of the kid’s project that I’m working on, and the amount of time I spend with my son, everything seems to be making its way through that filter. Truth be told there actually has been some amazing design that has occurred in the kid’s space, but a lot of the good stuff is no longer in production, only in Europe, or just hard to track down. I recently tracked down Enzo Mari’s catalog from his recent show curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist in Milan, and am just blown away by his output, especially the pieces he made for children.

Top 3 design books?

The Hot House: Italian New Wave Design by Andrea Branzi. Martino Gamper’s 100 Chairs in 100 Days. Italy: The New Domestic Landscape (MOMA).

Lastly, now that you’ve been residing in Los Angeles for a few years, what’s your take on the design community here? Ideally, how do you see it developing?

LA is a special place with so much history and talent spanning a lot of industries. Compared to the major European cities, and New York, I think the design scene is a relatively small community. Not to throw any shade on artists (most of my friends are artists), but I’ve found the design community a lot more open and generous with their time, contacts, and resources than when I was solely focused on making and exhibiting art as an artist. I think there is a lot of potential for LA to become a global design center, but it’s not going to happen overnight. Things seem to move at a slower pace here, which I think is actually a good thing.

Spiritual Leader

Sardines, tulips, paint pallets, and Disco’s eighth-note. These are the Spiritual Objects of Los Angeles based designer and artist Luc Fuller. A Pacific Northwest transplant, he’s approaching design through a new lens of parenting, though his work has always been whimsical.

Fuller’s design path has been an uninterrupted stream of adventure. Whether reclined in his old Jeep listening to John Coltrane as a teenager, meeting new design friends in questionable attire (more on that later), or learning his commissioned Tulip Table (that seats ten) provided a dance floor for an afterparty, there is an improvisational thread in his work.

A thread that not only blurs the line between artful and functional objects, but transcends it, like A Love Supreme. Coltrane’s “through-composed” album and Fuller’s creative work share a continuous, non-sectional, and non-repetitive nature, making myth of the everyday.

You grew up in the Pacific North West? Tell us about family life and growing up there.

When I think about growing up in the Northwest I think about being outside: riding bikes, swimming, camping, fishing, and spending time in the mountains. Coming from a large family (my dad is one of seven), I spent a lot of time with my cousins, aunts, and uncles. Interestingly, my parents actually grew up in Southern California but moved north after college. Eventually, all of my aunts, uncles, and grandparents followed suit and moved to Washington State, while I somehow ended up back in LA.

Were you drawn to art and design in your teenage years or did that come a bit later? What music, books or films stand out from this period?

I was definitely an art kid. Although I tried my hand at various sports, once I started playing music and taking art classes in middle school, everything else took a backseat. Without those art classes, I doubt I would have graduated high school.

It wasn’t until college that I had the opportunity to visit my first art museum beyond the small regional museum in Spokane. The lack of an immediately accessible visual culture in my hometown led to an unquenchable curiosity within me, which I still feel today.

Discovering something for the first time whether it’s from a hundred years ago, or yesterday, is a high that I’m constantly trying to get back to. I vividly remember the first time I listened to John Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme” in high school. My friend Ian insisted that we skip class and listen to it uninterrupted. We were sitting in my old Jeep with reclined seats, at a nearby park.

How did your work develop at Pacific Northwest College of Art and did you form a studio practice straight after?

PNCA was an excellent school. The undergraduate program resembled an MFA program, where our final year involved working with a mentor and developing a thesis that we had to defend. Interestingly, this academic approach to art and creativity contrasts with my current view of my practice. After graduating, I felt a strong sense of guilt for simply wanting to create things for the sake of creating. I think I’m just now getting to a place feeling comfortable in my own skin and not feeling any sense of shame or pressure to do anything other than go about things my own way.

Your work around this time was primarily focused around paint, inkjet prints, and photographs. What other processes were you exploring then?

My work was all over the place! Looking back, I see that I was gradually pushing the boundaries of “painting” and “art,” exploring adjacent cultural realms such as fashion, music, and later, design. I can’t say it was the most interesting work on the planet, but it was a start.

“Three of my heroes—Franz West, Donald Judd, and Mary Heilmann—have all explored making functional objects in addition to their artistic pursuits.”

When did you transition into making objects and when was ‘Spiritual Objects’ born? Is the model rooted in this idea of ‘Everyday Objects?’

I believe the seed was planted while my wife and I were living in Copenhagen between 2015 and 2016. Design in Denmark, as well as many other parts of Europe, seamlessly integrates into everyday life. I found myself leaving museums equally inspired by the furniture, lighting, and architecture as I was by the art.

Moreover, many of my favorite artists have, at some point, created useful and functional objects, which always fascinated me. Three of my heroes—Franz West, Donald Judd, and Mary Heilmann—have all explored making functional objects in addition to their artistic pursuits.

In my perspective, the integration of functional objects into the realm of art blurs boundaries, resulting in art somehow becoming more accessible and human. Simultaneously, this fusion allows furniture and objects to surpass their mere practical utility and offer something deeper or more meaningful as well.

For me, getting into design was a gradual process. I kept it a secret for a couple of years while taking furniture design night classes at Art Center in Pasadena and setting up a small workshop in our garage.

I officially launched Spiritual Objects in the fall of 2019 with a small collection that included the Disco Stool, the Sardine, and the Cutting Board. My goal was to create a platform that would grant me autonomy from the gallery world and allow me to create things I felt genuinely excited about, regardless of fitting neatly into a specific category.

Today, after nearly four years, Spiritual Objects operates as a design studio, an art practice, and a brand. Our projects encompass product design, furniture design, custom commissions, illustration, and occasional exhibitions.

“The after-party got completely out of hand and I learned the next morning that people were dancing on some of the tables, including mine.”

In recent years, are there any favorite pieces or notable commissions you’ve created that stand out?

I don’t have any particular favorites per se. For me, the connection to my work lies in what each product or project teaches me. With every new creation, new challenges arise, and I discover my preferences and dislikes regarding processes, materials, and approaches.

Last summer, I had the opportunity to design a large sculptural table for Copenhagen’s annual design festival, 3daysofdesign. Five designers/studios from five different countries were commissioned, with the only requirement being its functionality and ability to seat ten guests for a dinner party.

The whole project was an absolute blast, and eating dinner on my giant tulip-shaped table, sitting directly across from Carin Panton von Halem (designer Verner Panton’s daughter) is an experience I’ll never forget!

In typical Copenhagen fashion, the after-party got completely out of hand and I learned the next morning that people were dancing on some of the tables, including mine. To be honest, I don’t know what more I could have asked for.

You’re also developing a new project that is looking to fill a gap in the kids furniture market. Can you shed some light on this new venture?

I’m sure I’m not the first designer to have kids and suddenly want to start designing kids’ products, but it’s something that I couldn’t help exploring being both inspired by spending time with my son and disappointed by the lack of interesting products on the market. It’s still early days but the process has been quite fun, and I think natural for me as my work already has a playful simplicity embedded in everything I make. The project is also another excuse to work with other creatives, and eventually work with other designers as well to develop products.

“I recently tracked down Enzo Mari’s catalog from his recent show curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist in Milan.”

We can’t wait to see what you produce. Shifting to travel, as you’re the adventurous type, you had a pretty interesting exhibition in London, where we share mutual friends, right?

That first trip to London where I met our mutual friend Nick Bell changed my life.

I was there for about 5 weeks, painting, and preparing for my first proper solo exhibition at Rod Barton in Peckham. The gallery put me up at a nearby shared Airbnb, which happened to be Nick’s flat. I remember arriving in London really late and Nick and his flatmates left me a key because they were out partying.

When I woke up and went downstairs I saw Nick and one of his friends out in the garden, still up from the night before, half-naked in a fur coat, in full makeup. While still slightly under the influence of who knows what, he welcomed me as if we were family and proceeded to make me one of the worst coffees I’d ever had in my life. We’ve been best friends ever since!

That’s a vivid scene. What’s caught your curious eye as of late?

I think because of the kid’s project that I’m working on, and the amount of time I spend with my son, everything seems to be making its way through that filter. Truth be told there actually has been some amazing design that has occurred in the kid’s space, but a lot of the good stuff is no longer in production, only in Europe, or just hard to track down. I recently tracked down Enzo Mari’s catalog from his recent show curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist in Milan, and am just blown away by his output, especially the pieces he made for children.

Top 3 design books?

The Hot House: Italian New Wave Design by Andrea Branzi. Martino Gamper’s 100 Chairs in 100 Days. Italy: The New Domestic Landscape (MOMA).

Lastly, now that you’ve been residing in Los Angeles for a few years, what’s your take on the design community here? Ideally, how do you see it developing?

LA is a special place with so much history and talent spanning a lot of industries. Compared to the major European cities, and New York, I think the design scene is a relatively small community. Not to throw any shade on artists (most of my friends are artists), but I’ve found the design community a lot more open and generous with their time, contacts, and resources than when I was solely focused on making and exhibiting art as an artist. I think there is a lot of potential for LA to become a global design center, but it’s not going to happen overnight. Things seem to move at a slower pace here, which I think is actually a good thing.