Found Abstractions

Kristopher Raos builds his world from the edges of the city – fragments, colors, half-seen moments gathered in passing. His paintings feel slow, distilled, pulled from lived experience and memory. From Bakersfield to Mexico City to Los Angeles, he turns the overlooked into something strangely charged and deeply intentional.

Growing up between Bakersfield and Mexico City – how did those two different visual cultures feed into your aesthetic DNA?

Growing up in two very different places could not have been more contrasting. Bakersfield was very flat and almost desolate, especially in the neighborhood where I grew up, compared to the time I spent in Mexico City. Recently, I realized I got to experience Mexico City quite literally from the passenger seat, as I used to do taxi routes with my uncles. I was able to absorb all the density of the city through a “Route,” if you will.

You’ve mentioned that seeing Ellsworth Kelly at MOCA back in 2007 was a turning point. What did that encounter with Minimalism and hard-edge abstraction open up for you?

Seeing Ellsworth Kelly’s work in person for the first time had a profound effect on me. Up to that point, he was an artist I had only discovered in textbooks during an art history class. When I flipped the page and saw his and Frank Stella’s work, I immediately questioned how this could possibly be considered art worthy of a place in the history books. I will admit that around that same time, I had already started leaning towards reduction and questioning what truly constitutes a finished graffiti piece. Maybe it was that moment that encouraged me to continue working with restraint and focus on the essentials.

“There’s this inertia I experience with my lived environment – a constant shifting, breaking down, and discarding of its old self.”

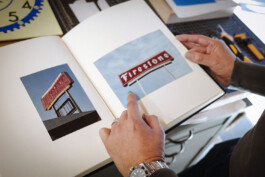

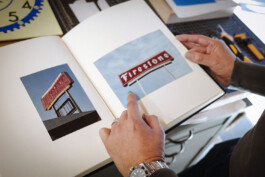

You draw on commercial iconography, logos, street signage, urban fragments – what catches your eye in the first place?

I want to clarify that I’m not necessarily interested in typography or signs specifically; after all, I didn’t study typography, graphic design, or sign painting. Be that as it may, I’ve spent a lot of time designing letter styles when I was doing graffiti, but I wouldn’t consider myself an expert in any of those fields. However, I like to think that what draws me to the subject matter is the sense that I’m capturing things in my periphery as I move through my environment, always doing a double or triple take. It’s usually color and form that catch my eye, and there’s also this inertia I experience with my lived environment — a constant shifting, breaking down, and discarding of its old self. I’m just in a perpetual dumpster dive; one man’s trash is my next abstraction.

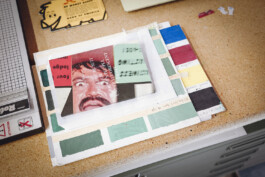

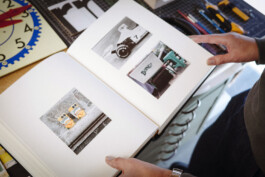

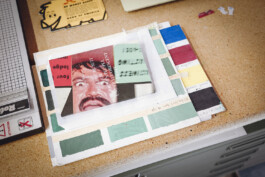

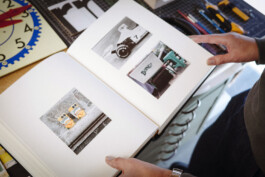

You move from photos to studies to fragments to paintings – almost like distilling the world into its most charged shapes. What tells you a fragment has the energy to make that final leap onto canvas?

I’m sourcing subject matter mostly by chance, whether I’m commuting, walking, or occasionally online. I would say, by all accounts, I’m still working with a traditional medium I’ve come to accept it has its limitations. I enjoy working with as little information as possible. The things that tend to stick with me and go on to become paintings can be pliable; it’s never exactly how I plan it. I feel like I learn something each time I start a new painting or sculpture.

“I’m just in a perpetual dumpster dive; one man’s trash is my next abstraction.”

Your exhibition titles are all pulled from hip hop albums. What’s the connection for you between those songs and the work?

I grew up listening to hip-hop music in the 90s through the early aughts. Many of my experiences as a young person really resonated with what I heard in the music. While some people grow up with art in their homes or visit museums and galleries at a very young age, I believe music, especially hip-hop, was my equivalent. It was my first taste of creative thinking and gave me, even if only for a brief moment, a way to escape my circumstances at the time.

At one point your landlord was a Ferrari mechanic, and that relationship sparked an entire body of work. What was it about his world – the tools, the surfaces, the signage – that pulled you in?

Yeah, my landlord was a mechanic for Ferrari in the 70s on the F1 circuit. He came by one time and noticed that I had painted a 911 in the Porsche (90s era) font, and from that moment on, anytime he’d visit, he would talk about his time working as a mechanic for Ferrari. There was a time I asked him what it would take to become a professional Formula One driver, and in short, he said you’d have to start very early, have contacts, and above all, “Mucha Plata” — lots of money. For a second, I forgot we were talking about racing and could have sworn we were talking about being a blue-chip artist! His name was Tony. He was such a generous landlord, kept our rent affordable, and shared so much lore about Los Angeles and Echo Park. The body of work was almost like an ode to him in many ways. A lot of the material I collected was directly from ephemera he gifted or shared with me. I wouldn’t normally engage with that kind of material for fear it might look like man-cave art, but once it started to be tied to the story and landscape of Los Angeles, it very quickly felt intertwined. He gave me a really cool picture of Paul Newman and himself leaning atop a car in the pit — such an iconic shot!

You’ve just moved into a new studio. How has the space changed the way you work – the light, the scale, the energy?

It’s been relatively recent that I’ve been in the new space, about three months, and only in the last month have I been able to make new work. This is my biggest studio to date; I can finally stand more than 8 feet away from the wall, which has completely changed my workflow. I can spread out more and get a better sense of the scale of one piece in relation to another. In my previous space, it was a one-large-painting-at-a-time ordeal! It’s still too early to see how the space will benefit my process over time, although the high ceilings and large south-facing windows make the studio feel very dreamy!

You’ve spoken about taking your time with the work – really embracing slowness. What does moving at that pace give you creatively?

I work with very thin, saturated layers of paint, almost like staining, so I feel like the process demands a slow, meditative approach. There are also thicker, built-up embossed details, which by their very nature require time to dry between layers to achieve the final result. In many ways, because the material isn’t readily sourced and is never one-to-one, it could be compared to mass production and commodities. I like turning that idea on its head to push back against the notion that artists have to be prolific producers of work or products. But frankly, three of my favorite living artists working in painting have all established an affinity for working slowly but undoubtedly, each prolific in their own pursuit. There’s no rush with this thing.

“There’s this feeling of wanting to preserve or breathe new life into something forgotten.”

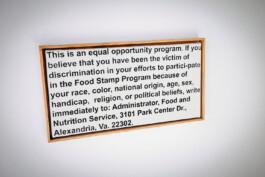

You’ve talked about working over the top of other artists’ murals or bits of existing signage – almost a quiet dialogue with what’s already there. Do you see that as connected to your graffiti roots?

Yeah, maybe it’s connected to the sensibility I developed while doing graffiti, of course observing my environment. But instead of thinking about where I could plaster my moniker now, there’s this feeling of wanting to preserve or breathe new life into something that seems forgotten or discarded.

As you build toward Frieze next year, what ideas or fragments are starting to surface? Anything that feels like a shift from the recent work?

I’m not sure I fully understand how I personally see my work in a fair environment. It’s not my favorite place to experience artwork, but I recognize the validity of the venue from a commercial perspective. The work I’m doing for Frieze feels like a continuation of a body of work called “Can I Live” that I did for a show at the beginning of 2025 with Charlie James Gallery. There are some old details and techniques that I’m revisiting, which feels exciting!

You’ve been in LA for a while now. What’s your take on the creative community here – the energy, the conversations, the way people move around each other?

I’ve been in LA for almost 15 years. The whole time, it’s been Kat and I; we came here together and have been together ever since. I think we’ve been fortunate to get to discover the creative community in the city in such an organic way that over those 15 years, the city has always found new ways to surprise me. I believe we’ve been fortunate to connect with Los Angeles through our individual practices. For me, I feel linked to the work that happens here in many ways, and I see Los Angeles as a very working-class city. I feel a purpose in what I do here, in this eclectic mishmash of a city.

Found Abstractions

Kristopher Raos builds his world from the edges of the city – fragments, colors, half-seen moments gathered in passing. His paintings feel slow, distilled, pulled from lived experience and memory. From Bakersfield to Mexico City to Los Angeles, he turns the overlooked into something strangely charged and deeply intentional.

Growing up between Bakersfield and Mexico City – how did those two different visual cultures feed into your aesthetic DNA?

Growing up in two very different places could not have been more contrasting. Bakersfield was very flat and almost desolate, especially in the neighborhood where I grew up, compared to the time I spent in Mexico City. Recently, I realized I got to experience Mexico City quite literally from the passenger seat, as I used to do taxi routes with my uncles. I was able to absorb all the density of the city through a “Route,” if you will.

You’ve mentioned that seeing Ellsworth Kelly at MOCA back in 2007 was a turning point. What did that encounter with Minimalism and hard-edge abstraction open up for you?

Seeing Ellsworth Kelly’s work in person for the first time had a profound effect on me. Up to that point, he was an artist I had only discovered in textbooks during an art history class. When I flipped the page and saw his and Frank Stella’s work, I immediately questioned how this could possibly be considered art worthy of a place in the history books. I will admit that around that same time, I had already started leaning towards reduction and questioning what truly constitutes a finished graffiti piece. Maybe it was that moment that encouraged me to continue working with restraint and focus on the essentials.

“There’s this inertia I experience with my lived environment – a constant shifting, breaking down, and discarding of its old self.”

You draw on commercial iconography, logos, street signage, urban fragments – what catches your eye in the first place?

I want to clarify that I’m not necessarily interested in typography or signs specifically; after all, I didn’t study typography, graphic design, or sign painting. Be that as it may, I’ve spent a lot of time designing letter styles when I was doing graffiti, but I wouldn’t consider myself an expert in any of those fields. However, I like to think that what draws me to the subject matter is the sense that I’m capturing things in my periphery as I move through my environment, always doing a double or triple take. It’s usually color and form that catch my eye, and there’s also this inertia I experience with my lived environment — a constant shifting, breaking down, and discarding of its old self. I’m just in a perpetual dumpster dive; one man’s trash is my next abstraction.

You move from photos to studies to fragments to paintings – almost like distilling the world into its most charged shapes. What tells you a fragment has the energy to make that final leap onto canvas?

I’m sourcing subject matter mostly by chance, whether I’m commuting, walking, or occasionally online. I would say, by all accounts, I’m still working with a traditional medium I’ve come to accept it has its limitations. I enjoy working with as little information as possible. The things that tend to stick with me and go on to become paintings can be pliable; it’s never exactly how I plan it. I feel like I learn something each time I start a new painting or sculpture.

“I’m just in a perpetual dumpster dive; one man’s trash is my next abstraction.”

Your exhibition titles are all pulled from hip hop albums. What’s the connection for you between those songs and the work?

I grew up listening to hip-hop music in the 90s through the early aughts. Many of my experiences as a young person really resonated with what I heard in the music. While some people grow up with art in their homes or visit museums and galleries at a very young age, I believe music, especially hip-hop, was my equivalent. It was my first taste of creative thinking and gave me, even if only for a brief moment, a way to escape my circumstances at the time.

At one point your landlord was a Ferrari mechanic, and that relationship sparked an entire body of work. What was it about his world – the tools, the surfaces, the signage – that pulled you in?

Yeah, my landlord was a mechanic for Ferrari in the 70s on the F1 circuit. He came by one time and noticed that I had painted a 911 in the Porsche (90s era) font, and from that moment on, anytime he’d visit, he would talk about his time working as a mechanic for Ferrari. There was a time I asked him what it would take to become a professional Formula One driver, and in short, he said you’d have to start very early, have contacts, and above all, “Mucha Plata” — lots of money. For a second, I forgot we were talking about racing and could have sworn we were talking about being a blue-chip artist! His name was Tony. He was such a generous landlord, kept our rent affordable, and shared so much lore about Los Angeles and Echo Park. The body of work was almost like an ode to him in many ways. A lot of the material I collected was directly from ephemera he gifted or shared with me. I wouldn’t normally engage with that kind of material for fear it might look like man-cave art, but once it started to be tied to the story and landscape of Los Angeles, it very quickly felt intertwined. He gave me a really cool picture of Paul Newman and himself leaning atop a car in the pit — such an iconic shot!

You’ve just moved into a new studio. How has the space changed the way you work – the light, the scale, the energy?

It’s been relatively recent that I’ve been in the new space, about three months, and only in the last month have I been able to make new work. This is my biggest studio to date; I can finally stand more than 8 feet away from the wall, which has completely changed my workflow. I can spread out more and get a better sense of the scale of one piece in relation to another. In my previous space, it was a one-large-painting-at-a-time ordeal! It’s still too early to see how the space will benefit my process over time, although the high ceilings and large south-facing windows make the studio feel very dreamy!

You’ve spoken about taking your time with the work – really embracing slowness. What does moving at that pace give you creatively?

I work with very thin, saturated layers of paint, almost like staining, so I feel like the process demands a slow, meditative approach. There are also thicker, built-up embossed details, which by their very nature require time to dry between layers to achieve the final result. In many ways, because the material isn’t readily sourced and is never one-to-one, it could be compared to mass production and commodities. I like turning that idea on its head to push back against the notion that artists have to be prolific producers of work or products. But frankly, three of my favorite living artists working in painting have all established an affinity for working slowly but undoubtedly, each prolific in their own pursuit. There’s no rush with this thing.

“There’s this feeling of wanting to preserve or breathe new life into something forgotten.”

You’ve talked about working over the top of other artists’ murals or bits of existing signage – almost a quiet dialogue with what’s already there. Do you see that as connected to your graffiti roots?

Yeah, maybe it’s connected to the sensibility I developed while doing graffiti, of course observing my environment. But instead of thinking about where I could plaster my moniker now, there’s this feeling of wanting to preserve or breathe new life into something that seems forgotten or discarded.

As you build toward Frieze next year, what ideas or fragments are starting to surface? Anything that feels like a shift from the recent work?

I’m not sure I fully understand how I personally see my work in a fair environment. It’s not my favorite place to experience artwork, but I recognize the validity of the venue from a commercial perspective. The work I’m doing for Frieze feels like a continuation of a body of work called “Can I Live” that I did for a show at the beginning of 2025 with Charlie James Gallery. There are some old details and techniques that I’m revisiting, which feels exciting!

You’ve been in LA for a while now. What’s your take on the creative community here – the energy, the conversations, the way people move around each other?

I’ve been in LA for almost 15 years. The whole time, it’s been Kat and I; we came here together and have been together ever since. I think we’ve been fortunate to get to discover the creative community in the city in such an organic way that over those 15 years, the city has always found new ways to surprise me. I believe we’ve been fortunate to connect with Los Angeles through our individual practices. For me, I feel linked to the work that happens here in many ways, and I see Los Angeles as a very working-class city. I feel a purpose in what I do here, in this eclectic mishmash of a city.