Off Balance

David Shull has this way of making everything – surfing, music, charcoal, even low-fi sculpture – feel like part of the same long conversation he’s having with himself. Nothing rushed, nothing forced. Just steady curiosity, a little salt air in the background, and an artist quietly figuring out what comes next.

You grew up in Ventura, a coastline of surf, salt air, and quiet freedom. What do you remember most vividly about that place, and how did it shape your early visual language?

My mother, little sister, and I moved to the east end of Ventura from Dana Point the summer before I entered 4th grade. Honestly, the circumstance shaped me more than the place. My sister and I were latch-key kids, so from an early age I had a little more responsibility than my peers. My memories of early life in Ventura are really centered around our little family unit. But Ventura was a nice place to grow up – a sleepy little beach town, very safe. We could walk to school, play in the street, etc.

In middle school my friends and I started getting rides to the beach to go bodyboarding and eventually surfing. That was a big shift – surfing and being in the ocean became a sort of obsession.

“Surfing is mostly sitting alone, staring at the horizon.”

Surf culture is built on improvisation, reading waves, and balancing chaos with grace. Do you recognize any of that rhythm or instinct in your studio practice today?

The one thing surfing and art-making really have in common is solitude. When people think about surfing, they think about riding waves, but the vast majority of surfing is sitting on your board alone, silently staring out at the ocean. Despite its connection to sport and maybe related to a sort of spiritual thing that’s rooted to an intimacy with nature, surfing is actually quite a contemplative activity.

Also, surfing requires perseverance. You get up early, put on a wet wetsuit in the cold, endure wave after wave paddling out, fall, try again… It’s a ton of effort for a few 5–10 second rides. Being an artist can feel like that sometimes.

Your mother was a quilt maker who worked with repetition, pattern, and color. How does that kind of handmade logic or tactile storytelling show up in your work now?

If you go to a quilt show, you’ll find such an array of intentions – a quilt made for a husband with tool-themed or golf-themed fabric, quilts made for babies, quilts made from T-shirt collections, etc. They’re often made as gifts. But all quilts lean on this rich cultural tradition – patterns developed and passed down between generations of women. There’s a beautiful humility in not constantly trying to reinvent the wheel. Quilt makers don’t have this Freudian “kill the father” thing. And, like you said, they’re handmade – that’s the whole point in a way. Being creative is simply a wonderful way to spend your time.

I feel that in the studio sometimes – my time there isn’t geared toward finishing pieces. When something is finished I may feel pride or accomplishment, but then I’m putting it down and starting something new.

Art, especially high art, can be an intellectual gymnastics competition – part of me enjoys that, but it can also be paralyzing. I feel best in the studio when I can lower the stakes and act intuitively while acknowledging that I’m standing on the shoulders of ancestors. I don’t make my work for a specific viewer. I’m working something out that I can’t quite describe or define. There was a time when I wanted to be the smartest or most sensitive or perceptive person in the room. Now it’s flipped – I’m trying to learn something. I want to get my ego out of the way.

You’re also a musician. Does the repetition and structure of music – loops and rhythm – influence the way you build or layer your visual compositions?

Music was definitely my first love. If there’s a relationship to my art, it’s probably somewhere in the ether – the tradition, the poetry, the sonic texture, the cultural connections. It’s very difficult to talk about. Some people would call it “god” or “love.” I think of it as an indelible connective tissue. Art-making, like music-making, can be a kind of time machine – we can have conversations cross-culturally and across space and time.

What were some of the key bands or music projects you were involved with over the years?

I was in a few bands when I was living in NY. One was a kind-of subdued post-punk project called Left Coast with my friends Lane Lacolla and Sarah Frances. I played drums in an amazing band called The Poison Dartz, which centered around songs written by Alan Lewandowski. Shortly before I left NY, I had a band called The Seashellz. During my first years in LA I had a band called The Soft Dartz, which was kind of an a cappella thing.

“Art-making can be a kind of time machine.”

You spent time living in New York. How would you describe that chapter of your life?

New York marked the beginning of me centering art in my life. I studied biology at UC Santa Cruz and moved to New York when I was 23 to study at Pratt. At the time, I wanted to get away from California – away from beach culture. I wanted to see the world and be around other creative people. It’s like how people say it’s difficult to change when you’re in long relationships – I didn’t feel like I could find my future self in Southern California. I needed to leave, and I was really fortunate to find an incredible community in NY.

A project with Hauser & Wirth brought you back to Los Angeles where you eventually stayed. What did you take away from working inside a major gallery system, and when did you decide to fully commit to your own practice?

I fully committed to my art practice fairly early on. While finishing my biology degree in Santa Cruz, I had a moment of clarity. I didn’t really grow up around art. My mom had framed posters of Georgia O’Keeffe and Van Gogh, which I loved. She also had a book about The Dinner Party by Judy Chicago. But I didn’t know anyone living as an artist. I hadn’t been to many museums. I couldn’t wrap my head around what it meant to “be an artist.” I started making paintings in my bedroom on a whim when I was 19 and fell in love.

After graduate school I had, what felt like, a million jobs – film and video production, restaurant work, personal driver for a fashion mogul, art handling, studio assistant work, etc. I was afraid to take full-time work because I was afraid of the time commitment. But working at the gallery provided me with so much. It was a gift to meet and work with so many amazing artists.

I moved to LA to help set up the enormous Hauser & Wirth LA gallery from scratch. It was a herculean effort, but we had a great team and I’m proud of what we accomplished. It can be a bit demystifying to see how the sausage is made, but I found working at the gallery extremely inspiring.

Tell me about your recent show at NOON titled FLHAT EARTH FALLING WATER. Where did that body of work begin and what unlocked it for you as the series took shape?

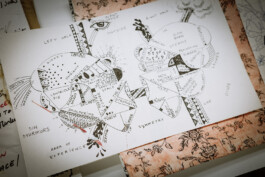

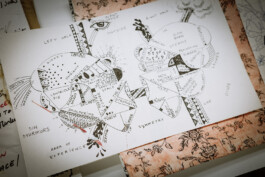

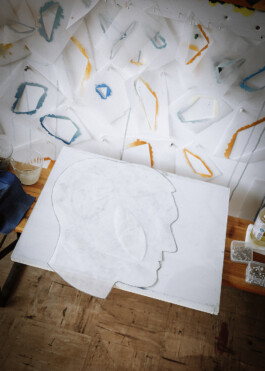

From time to time I flip through old sketchbooks for inspiration – I’ve found that my work revolves around this forward-and-back process. I came across a doodle I made about 10 years ago of a bunch of hats with the text “an artist wears many hats.” Each hat was different – a romantic hat made of hearts, a carpenter hat made of boards and nails, a muscleman hat with biceps growing out of it. There’s a kind of threshold that needs to be met for me to act on an idea, and the hats felt like a strong enough armature to explore.

I’d also been wanting to remove color through charcoal drawings and make a concise exhibition. It was exciting to see how the cowboy hat – a symbol of this overconfident American libertarian thing – could be used to expose an underlying frailty. FLHAT EARTH FALLING WATER came out of that.

You have another show coming up at NOON. What can you share about that?

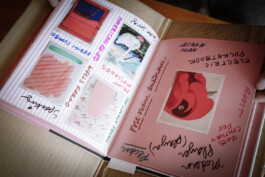

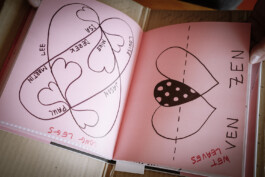

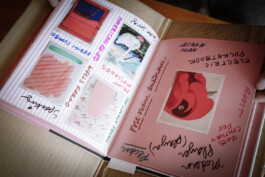

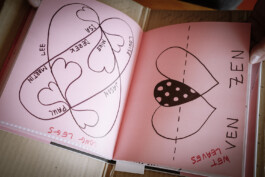

I’m really excited about this show. I’ll be releasing a book I’ve been working on since 2010 called Where There Is Great Love There Are Always Great Miracles. The book documents work I made between 2002 and 2009 – sculptures, paintings, drawings, and assemblages – that I was proud of but never had the chance to show. I collaborated with my friend Jack Doroshow on the text, which is graffiti’d across the 150 pages, and which I hand-transcribed in the 21 copies.

Alongside the book, we’ll install a selection of these works. It’s strange but deeply satisfying to revisit that period of my life and finally share this work.

“I’m trying to get my ego out of the way and learn something.”

What is happening musically in your world right now?

Earlier this year I dedicated a month of my studio practice to recording a new album. Shortly after the pandemic, one of my best friends – my primary musical collaborator in LA – tragically passed away. It was really difficult and led to a bit of a musical hiatus. It was cathartic to get back on the horse and record. My friend Dan Gower and I are mixing it now and hope to put out a cassette tape in early 2026. I’m not really interested in playing shows at the moment, but it feels good to be playing again.

What is pulling you forward creatively at the moment?

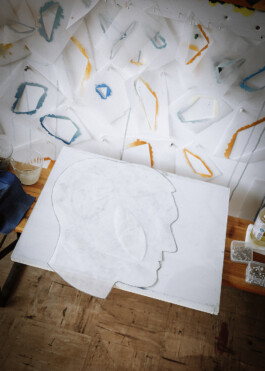

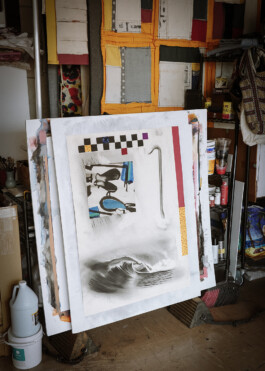

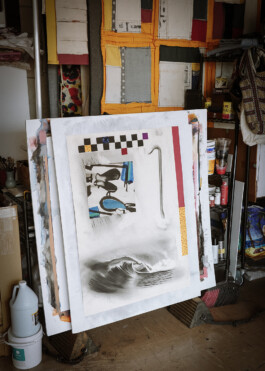

I think I’m pulled forward through the process of making – setting up problems, whether compositionally or materially, and trying to resolve them. Much of the work in the book is really low-fi sculpture, which has been exciting to revisit. I recently started oil painting for the first time and am trying to reconcile that with the charcoal drawing and fabric assemblage work I’ve been making over the past few years. So things are a bit experimental at the moment.

I used to chase some big perfect idea, but now I’m learning the value of the process itself. Art gives me a tremendous sense of purpose – I’m just trying to fulfill that every day.

Off Balance

David Shull has this way of making everything – surfing, music, charcoal, even low-fi sculpture – feel like part of the same long conversation he’s having with himself. Nothing rushed, nothing forced. Just steady curiosity, a little salt air in the background, and an artist quietly figuring out what comes next.

You grew up in Ventura, a coastline of surf, salt air, and quiet freedom. What do you remember most vividly about that place, and how did it shape your early visual language?

My mother, little sister, and I moved to the east end of Ventura from Dana Point the summer before I entered 4th grade. Honestly, the circumstance shaped me more than the place. My sister and I were latch-key kids, so from an early age I had a little more responsibility than my peers. My memories of early life in Ventura are really centered around our little family unit. But Ventura was a nice place to grow up – a sleepy little beach town, very safe. We could walk to school, play in the street, etc.

In middle school my friends and I started getting rides to the beach to go bodyboarding and eventually surfing. That was a big shift – surfing and being in the ocean became a sort of obsession.

“Surfing is mostly sitting alone, staring at the horizon.”

Surf culture is built on improvisation, reading waves, and balancing chaos with grace. Do you recognize any of that rhythm or instinct in your studio practice today?

The one thing surfing and art-making really have in common is solitude. When people think about surfing, they think about riding waves, but the vast majority of surfing is sitting on your board alone, silently staring out at the ocean. Despite its connection to sport and maybe related to a sort of spiritual thing that’s rooted to an intimacy with nature, surfing is actually quite a contemplative activity.

Also, surfing requires perseverance. You get up early, put on a wet wetsuit in the cold, endure wave after wave paddling out, fall, try again… It’s a ton of effort for a few 5–10 second rides. Being an artist can feel like that sometimes.

Your mother was a quilt maker who worked with repetition, pattern, and color. How does that kind of handmade logic or tactile storytelling show up in your work now?

If you go to a quilt show, you’ll find such an array of intentions – a quilt made for a husband with tool-themed or golf-themed fabric, quilts made for babies, quilts made from T-shirt collections, etc. They’re often made as gifts. But all quilts lean on this rich cultural tradition – patterns developed and passed down between generations of women. There’s a beautiful humility in not constantly trying to reinvent the wheel. Quilt makers don’t have this Freudian “kill the father” thing. And, like you said, they’re handmade – that’s the whole point in a way. Being creative is simply a wonderful way to spend your time.

I feel that in the studio sometimes – my time there isn’t geared toward finishing pieces. When something is finished I may feel pride or accomplishment, but then I’m putting it down and starting something new.

Art, especially high art, can be an intellectual gymnastics competition – part of me enjoys that, but it can also be paralyzing. I feel best in the studio when I can lower the stakes and act intuitively while acknowledging that I’m standing on the shoulders of ancestors. I don’t make my work for a specific viewer. I’m working something out that I can’t quite describe or define. There was a time when I wanted to be the smartest or most sensitive or perceptive person in the room. Now it’s flipped – I’m trying to learn something. I want to get my ego out of the way.

You’re also a musician. Does the repetition and structure of music – loops and rhythm – influence the way you build or layer your visual compositions?

Music was definitely my first love. If there’s a relationship to my art, it’s probably somewhere in the ether – the tradition, the poetry, the sonic texture, the cultural connections. It’s very difficult to talk about. Some people would call it “god” or “love.” I think of it as an indelible connective tissue. Art-making, like music-making, can be a kind of time machine – we can have conversations cross-culturally and across space and time.

What were some of the key bands or music projects you were involved with over the years?

I was in a few bands when I was living in NY. One was a kind-of subdued post-punk project called Left Coast with my friends Lane Lacolla and Sarah Frances. I played drums in an amazing band called The Poison Dartz, which centered around songs written by Alan Lewandowski. Shortly before I left NY, I had a band called The Seashellz. During my first years in LA I had a band called The Soft Dartz, which was kind of an a cappella thing.

“Art-making can be a kind of time machine.”

You spent time living in New York. How would you describe that chapter of your life?

New York marked the beginning of me centering art in my life. I studied biology at UC Santa Cruz and moved to New York when I was 23 to study at Pratt. At the time, I wanted to get away from California – away from beach culture. I wanted to see the world and be around other creative people. It’s like how people say it’s difficult to change when you’re in long relationships – I didn’t feel like I could find my future self in Southern California. I needed to leave, and I was really fortunate to find an incredible community in NY.

A project with Hauser & Wirth brought you back to Los Angeles where you eventually stayed. What did you take away from working inside a major gallery system, and when did you decide to fully commit to your own practice?

I fully committed to my art practice fairly early on. While finishing my biology degree in Santa Cruz, I had a moment of clarity. I didn’t really grow up around art. My mom had framed posters of Georgia O’Keeffe and Van Gogh, which I loved. She also had a book about The Dinner Party by Judy Chicago. But I didn’t know anyone living as an artist. I hadn’t been to many museums. I couldn’t wrap my head around what it meant to “be an artist.” I started making paintings in my bedroom on a whim when I was 19 and fell in love.

After graduate school I had, what felt like, a million jobs – film and video production, restaurant work, personal driver for a fashion mogul, art handling, studio assistant work, etc. I was afraid to take full-time work because I was afraid of the time commitment. But working at the gallery provided me with so much. It was a gift to meet and work with so many amazing artists.

I moved to LA to help set up the enormous Hauser & Wirth LA gallery from scratch. It was a herculean effort, but we had a great team and I’m proud of what we accomplished. It can be a bit demystifying to see how the sausage is made, but I found working at the gallery extremely inspiring.

Tell me about your recent show at NOON titled FLHAT EARTH FALLING WATER. Where did that body of work begin and what unlocked it for you as the series took shape?

From time to time I flip through old sketchbooks for inspiration – I’ve found that my work revolves around this forward-and-back process. I came across a doodle I made about 10 years ago of a bunch of hats with the text “an artist wears many hats.” Each hat was different – a romantic hat made of hearts, a carpenter hat made of boards and nails, a muscleman hat with biceps growing out of it. There’s a kind of threshold that needs to be met for me to act on an idea, and the hats felt like a strong enough armature to explore.

I’d also been wanting to remove color through charcoal drawings and make a concise exhibition. It was exciting to see how the cowboy hat – a symbol of this overconfident American libertarian thing – could be used to expose an underlying frailty. FLHAT EARTH FALLING WATER came out of that.

You have another show coming up at NOON. What can you share about that?

I’m really excited about this show. I’ll be releasing a book I’ve been working on since 2010 called Where There Is Great Love There Are Always Great Miracles. The book documents work I made between 2002 and 2009 – sculptures, paintings, drawings, and assemblages – that I was proud of but never had the chance to show. I collaborated with my friend Jack Doroshow on the text, which is graffiti’d across the 150 pages, and which I hand-transcribed in the 21 copies.

Alongside the book, we’ll install a selection of these works. It’s strange but deeply satisfying to revisit that period of my life and finally share this work.

“I’m trying to get my ego out of the way and learn something.”

What is happening musically in your world right now?

Earlier this year I dedicated a month of my studio practice to recording a new album. Shortly after the pandemic, one of my best friends – my primary musical collaborator in LA – tragically passed away. It was really difficult and led to a bit of a musical hiatus. It was cathartic to get back on the horse and record. My friend Dan Gower and I are mixing it now and hope to put out a cassette tape in early 2026. I’m not really interested in playing shows at the moment, but it feels good to be playing again.

What is pulling you forward creatively at the moment?

I think I’m pulled forward through the process of making – setting up problems, whether compositionally or materially, and trying to resolve them. Much of the work in the book is really low-fi sculpture, which has been exciting to revisit. I recently started oil painting for the first time and am trying to reconcile that with the charcoal drawing and fabric assemblage work I’ve been making over the past few years. So things are a bit experimental at the moment.

I used to chase some big perfect idea, but now I’m learning the value of the process itself. Art gives me a tremendous sense of purpose – I’m just trying to fulfill that every day.