Tranquil Activist

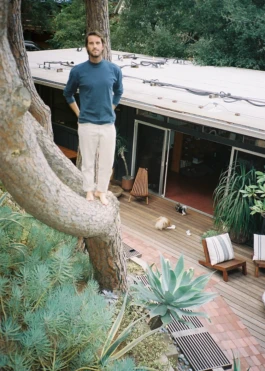

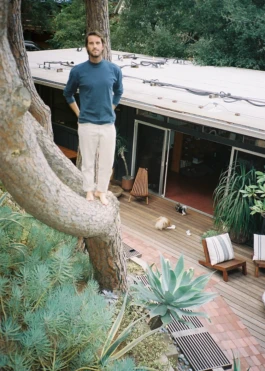

I met Daniel Jack Lyons at his home in Laurel Canyon which totally compliments his personality; calm, welcoming and perfectly considered. Daniel has been on quite the adventure thus far; born in Laguna Beach, a surfer, demonstrator, social anthropologist and documentary photographer. A creative spirit who's hell bent on raising awareness around social justice, human rights and LGBTQ liberation. Truly inspiring, what can I say, watch this space.

Tell me about growing up in Laguna Beach in the 80’s?

Almost – I was born in the 80s, but I came of age in the 90s. I feel pretty fortunate to have been born in Laguna Beach, and especially to have grown up there at that time. It was a very odd community of outsider artists, hippies, Motorcycle drug mafia, surfers, acid casualties and a vibrant gay community that held it all together.

I know you were into surfing during that period so what was the scene like then?

Surfing was just part of the culture. When I was 6 my mom started dropping me off at the beach everyday during summers – it was like a daycare. I don’t even remember learning to surf, it's just something that was passed on by older kids. I got really into skating as well and was sponsored by the local skate shop. But from when I was 13 I worked in a record store called Underdog Records, they only sold punk vinyl and tapes. It was illegal for me to work at that age, so I was paid in records. It's where I formed my first band, drank my first beer.. lots of firsts happened there. Laguna in general at that time was thriving; it wasn’t until the big fires of 93 when things started to change there. A lot of the artists lost their homes in the fire and left Laguna for good. Then HIV and AIDS hit really hard in the early 90s. Most of the gay community, the ones that didn’t die, sold their homes and moved to Palm Springs. That’s when the Orange County bourgeoisie started moving in, changing Laguna forever. I still love Laguna, especially the beaches and most of my family still lives there, but it feels like a very different town than when I grew up.

“I ran it by my friends, and they loved the idea of reclaiming and ultimately queerifying a space, particularly one where love is traditionally kept hidden.”

You started studying photography but then transitioned to more social and historical issues instead. Tell me about this period in your life, I believe at the same time you came out as being gay?

Yeah, I received a full ride artist scholarship to attend a university in Monterey, northern CA, which sat on an abandoned military base called Fort Ord. I was mostly interested in photography and sculpture. But then 2 things happened, 9-11 and I told all my friends that I’m gay. I quickly became immersed in radical queer politics and my artwork reflected that. I joineda guerilla art group called Gay Shame and started organizing protests in San Francisco. I became far more concerned with the political theories and histories that were driving my work than the work itself. So I left the art program, lost my scholarship and picked up a couple of catering jobs to pay the tuition. I got interested in social sciences since it related more directly activism. Eventuality, that’s what led me to move to Africa.

So you have a masters in Medical Anthropology and consult with human rights agencies correct? You also worked at the UN for a period of time?

Yes, after living in Mozambique for 4 years, I returned to the US and moved to New York, where I eventually got a Masters in Public Health, specifically in Medical Anthropology. I specialized in a research method called photovoice, which uses photography as a catalyst for anecdotal data. Essentially, I would give people cameras and interview them about the photos they take in relation to whatever human rights issue is being examined. I do this as a consultant and have worked several times with the UN and a number of other human rights agencies and NGOs.

When did you transition back into photography as a full-time profession?

It's kind of hard to say because when I left the art major, I continued to take photos. In fact, in some ways I took it more seriously because I was genuinely inspired. Throughout my years in Mozambique I continued to make portraits with people and take pictures. At that time I started thinking more seriously about long-form documentary and how to tell stories with my images as a series. But it wasn’t until after I moved to New York that I had some photos included in a few group exhibitions and my name got put out there, so to speak. That’s when I first started getting hired as a photographer. But as a full time profession, its been about 5 years now.

Who inspired you photographically around that period?

I’ve always been deeply inspired by Nan Goldin, I found an old copy of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency in the record store I worked at as a teenager, and it changed me forever. When I came out as gay, I really identified with the work of Catherine Opie and Philip Lorca DiCocia’s Hustlers series with male sex workers. But while living in Mozambique, I was obsessed with the work of Graciela Iturbide and Diane Arbus. And during my New York years I looked a lot at the work of David Armstrong, so much so that I had to stop looking at one point! There are so many more inspirations, but those are the big ones that come to mind.

In terms of your personal work there is obviously a direct correlation between your humanitarian interests and wonder how you come to find these very specific subject matters? Are these photographic essays typically different from your research work?

Yes and No. For a while I had this rhythm where I would get hired as a human rights research consultant to spend a month or longer in a country, working with a specific community about a very specific human rights or public health issue and while working on the project I would inevitably form personal relationships that would then tangentially inform my personal work in some way. Sometimes the subject matter of my personal work would correlate to my consulting work, but not always. I’m a big collaborator, so while documenting any group of people or community, I give space for them to have autonomy in defining the ultimate message that work conveys. And within that context, the work is also a reflection of my personal relationships. This was particularly true with Displaced Youth, the series I made in Ukraine with people/friends who had been displaced from the Russian invasion of Crimea. That project unfolded over a couple of years as I continued to meet incredible artists and musicians who warmly invited me into their world.

You also lived in Mozambique for a period of time and worked on a series of personal projects including Tech Girls Mahotas and Hotel Luso so can you tell me about the projects and your experiences at that time?

The irony is that I lived in Mozambique for 4 years from 04-08, but despite taking a lot of photos, I didn’t create work in the same way at that time – it was mostly portraits of friends and people that lived in my community. It wasn’t until 2014-18 that I made more focused work in Mozambique. I was on a contract with an organization there and was spending on average 5 months a year in Maputo, usually broken up into 6-8 weeks trips. It was during those years that I made Mahotas, Hotel Luso, and Tech Girls.

Mahotas was made with residents of a psychiatric hospital. I was working on a photovoice project that was examining the state of mental health services with clinical psychiatrists. Sadly, everyone was eager to show me just how terrible their clinic was, but there was one psychiatrist who quietly told me that she was quite proud of how her clinic operated. I visited the Mahotas clinic, which stood in contrast to the majority of psychiatric hospitals in Mozambique, extending its services beyond the standard in-patient psychosocial treatment to include a community reintegration program. This service included a form of occupational therapy in which patients are encouraged to engage in a range of activities including farming, gardening, animal husbandry, sewing, and artisanal crafting. The patients were excited to collaborate on a series, but I had some ethical concerns about how much they really understood the concept of publishing and exhibiting images. So together we came up with a way to protect their identity using an object, or in some cases an animal that is symbolic of their occupation within the hospital. The work was eventually exhibited as a solo show in Mozambique’s National Gallery in 2018.

Hotel Luso was a much more personal project for me, created with friends, some that I had known for over 10 years. Between 2005-08 I attended number of underground clandestine gay parties. The location would be announced at the last minute due to safety concerns. In those spaces I made some close friends, some of whom went on to found the first gay rights organization, an organization that the government still refuses to legally recognize. Mozambique is odd in that homosexuality is permissible by law, which keeps human rights lawyers at bay, however the social stigma is dangerously intense. To this end there are no gay spaces, no gay bars, no gay pride celebrations, and if an employer finds that someone is gay they can legally fire them, and with the advent of social media that happens more often. In 2017, while reconnecting with those same friends, they expressed interest in collaborating with me on a series that speaks to this dichotomy, but finding a way to tell that story was complicated. One morning I was walking through the “red light” district of Maputo, and struck up a conversation with the owner of a sex hotel. She told me that the hotel was mostly empty during daylight hours and I could rent the entire space for $6 an hour. I ran it by my friends, and they loved the idea of reclaiming and ultimately queerifying a space, particularly one where love is traditionally kept hidden. We rented the hotel several times over the course of a month. Participants brought with them flowers, lovers, and anything that aided in the kind of queer expression that is often denied to them in other spaces. A selection of this series was exhibited at RedHook Labs in 2018.

Hotel Luso – Daniel Jack Lyons

Also, most recently a project you’ve been working on in the Amazonian rain forest that speaks to both climate change and the rise of right wing authoritarianism?

Exactly, that’s the project I am immersed in now, and working on making into a monograph. This project began as a collaboration with Thiago Carvalo, a brazilian land activist and youth organizer. Thiago founded an organization called Casa Do Rio, which was initially intended to be an artist space to host residencies, but he received funding to focus on youth leadership programs, and that has been the organizations focus for the last 10 years. He came across my series, Displaced Youth and appreciated the way that series portrayed positive images of youth against a more somber socio-political backdrop. He hosted me as an artist in residence for 2 months in the summer of 2019. The process was pretty simple, it started with a big meeting of different groups of people – dancers, skaters, metal heads, etc. I presented a slide show of my work, introduced myself and the project. I explained that I work based on invitations and taped my number to the wall. Immediately my phone was exploding with messages and I didn’t stop for the entire 8 weeks. A lot of time was spent just hanging out with people long before I took out my camera. Everyone that participated chose how and where they wanted to be photographed, giving them autonomy in guiding the projects narrative. I was meant to go back this past summer and continue working on the series, however like so many things in 2020, plans changed.

Like a River – Daniel Jack Lyons

Now back to LA. How long have you been living in Laurel Canyon with your husband Nino and these beautiful dogs? And tell me about the area that of course is synonymous for its counterculture attitudes and has drawn in a multitude of creatives and musicians.

Technically I’ve lived in Laurel Canyon for 5 years, but I’ve only been in LA full time for the past 2 years. Laurel Canyon is cool. It’s got the obvious rich history of being home to Eric Burdon, the Byrds, Joni Mitchell, John Mayall, Brian Wilson, Neil Young, etc – I’m a big music nerd, so it’s appealing to me. But mostly I just love the peace and quiet. Especially after living in New York for so many years, Laurel Canyon makes me feel like I’m on an island of nature surrounded by an ocean of concrete.

And your beautiful mid-century home. When did you buy it? Did you make any major structural changes? I know you completely landscaped the whole garden?

My husband and I bought it in 2015. We haven’t touched anything inside the house. The only thing we’ve done is landscape the backyard, and create our dream garden. It’s been a fun process of slowly planting and playing in the dirt. My garden is a sanctuary to me, even in the winter I spend most of my time outside.

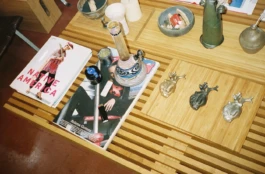

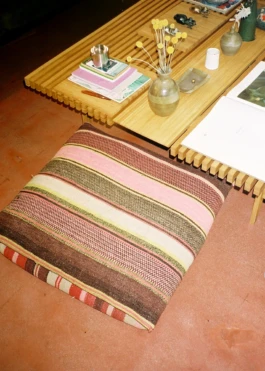

You’ve collected some beautiful furniture and artifacts as well, did you source most in Los Angeles, on your travels or both?

The house actually came with a lot of great mid century furniture. We acquired other things to fill the gaps from consignment and thrift stores here in LA. There are some artifacts from my travels scattered around, but most of the artwork, paintings, and pottery were all made by either family friends.

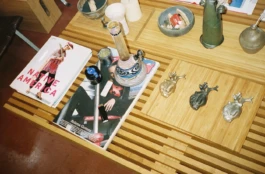

And your coffee table has become somewhat of an accidental shrine to your work?

Totally accidental! I probably shouldn’t say this, but I really don’t buy magazines anymore. So the only magazines and papers on the coffee table are the ones I’ve shot for!

I love your recent portrait of Paris Hilton for The New York Times and can imagine she was a rather unique subject matter?

Thank you so much. Yeah she was really kind, we mostly talked about dogs in between shots.

Any new ideas / projects in the pipeline? I’m presuming staying committed to exposing human rights, social justice and LGBTQ issues is something you’ll continue with?

I’m still really focused on my project in the Amazon, but in the last 2 years since spending more time in LA I’ve been working on a project here. I shot two bodies of work for the New York Times since being in LA, one that explored a predominantly Latino punk and hard core scene on the peripheries of Los Angeles. And the other documented queer performance artists that orbited a monthly party called Club SCUM in East LA. The two scenes have a lot of overlap and I’ve continued shooting both groups since the initial work was published. I find that so much of my other work is very structured and focused, which is important, but it’s a wonderful reprieve to work on something that has no timeline or direction, just organic image making with friends and their friends. And in doing so it’s opened up the opportunity for new directions in collaborating. For example, I recently created a project called ANIMA with a performance artist named DVVSK for Atmos. I initially met DVVSK while shooting the Club SCUM performers. We’ve stayed connected and over the first lockdown we came up with an idea for a project about becoming nature. I’m currently exploring other collaborations for publications with more people form that group as well. I’ve definitely found my queerdo community here in LA. But yes, I will always be committed to aligning my work with themes of social justice, human rights, and particularly LGBTQ liberation. I couldn’t change that if I tried, it’s in my DNA.

Tranquil Activist

I met Daniel Jack Lyons at his home in Laurel Canyon which totally compliments his personality; calm, welcoming and perfectly considered. Daniel has been on quite the adventure thus far; born in Laguna Beach, a surfer, demonstrator, social anthropologist and documentary photographer. A creative spirit who's hell bent on raising awareness around social justice, human rights and LGBTQ liberation. Truly inspiring, what can I say, watch this space.

Tell me about growing up in Laguna Beach in the 80’s?

Almost – I was born in the 80s, but I came of age in the 90s. I feel pretty fortunate to have been born in Laguna Beach, and especially to have grown up there at that time. It was a very odd community of outsider artists, hippies, Motorcycle drug mafia, surfers, acid casualties and a vibrant gay community that held it all together.

I know you were into surfing during that period so what was the scene like then?

Surfing was just part of the culture. When I was 6 my mom started dropping me off at the beach everyday during summers – it was like a daycare. I don’t even remember learning to surf, it's just something that was passed on by older kids. I got really into skating as well and was sponsored by the local skate shop. But from when I was 13 I worked in a record store called Underdog Records, they only sold punk vinyl and tapes. It was illegal for me to work at that age, so I was paid in records. It's where I formed my first band, drank my first beer.. lots of firsts happened there. Laguna in general at that time was thriving; it wasn’t until the big fires of 93 when things started to change there. A lot of the artists lost their homes in the fire and left Laguna for good. Then HIV and AIDS hit really hard in the early 90s. Most of the gay community, the ones that didn’t die, sold their homes and moved to Palm Springs. That’s when the Orange County bourgeoisie started moving in, changing Laguna forever. I still love Laguna, especially the beaches and most of my family still lives there, but it feels like a very different town than when I grew up.

“I ran it by my friends, and they loved the idea of reclaiming and ultimately queerifying a space, particularly one where love is traditionally kept hidden.”

You started studying photography but then transitioned to more social and historical issues instead. Tell me about this period in your life, I believe at the same time you came out as being gay?

Yeah, I received a full ride artist scholarship to attend a university in Monterey, northern CA, which sat on an abandoned military base called Fort Ord. I was mostly interested in photography and sculpture. But then 2 things happened, 9-11 and I told all my friends that I’m gay. I quickly became immersed in radical queer politics and my artwork reflected that. I joineda guerilla art group called Gay Shame and started organizing protests in San Francisco. I became far more concerned with the political theories and histories that were driving my work than the work itself. So I left the art program, lost my scholarship and picked up a couple of catering jobs to pay the tuition. I got interested in social sciences since it related more directly activism. Eventuality, that’s what led me to move to Africa.

So you have a masters in Medical Anthropology and consult with human rights agencies correct? You also worked at the UN for a period of time?

Yes, after living in Mozambique for 4 years, I returned to the US and moved to New York, where I eventually got a Masters in Public Health, specifically in Medical Anthropology. I specialized in a research method called photovoice, which uses photography as a catalyst for anecdotal data. Essentially, I would give people cameras and interview them about the photos they take in relation to whatever human rights issue is being examined. I do this as a consultant and have worked several times with the UN and a number of other human rights agencies and NGOs.

When did you transition back into photography as a full-time profession?

It's kind of hard to say because when I left the art major, I continued to take photos. In fact, in some ways I took it more seriously because I was genuinely inspired. Throughout my years in Mozambique I continued to make portraits with people and take pictures. At that time I started thinking more seriously about long-form documentary and how to tell stories with my images as a series. But it wasn’t until after I moved to New York that I had some photos included in a few group exhibitions and my name got put out there, so to speak. That’s when I first started getting hired as a photographer. But as a full time profession, its been about 5 years now.

Who inspired you photographically around that period?

I’ve always been deeply inspired by Nan Goldin, I found an old copy of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency in the record store I worked at as a teenager, and it changed me forever. When I came out as gay, I really identified with the work of Catherine Opie and Philip Lorca DiCocia’s Hustlers series with male sex workers. But while living in Mozambique, I was obsessed with the work of Graciela Iturbide and Diane Arbus. And during my New York years I looked a lot at the work of David Armstrong, so much so that I had to stop looking at one point! There are so many more inspirations, but those are the big ones that come to mind.

In terms of your personal work there is obviously a direct correlation between your humanitarian interests and wonder how you come to find these very specific subject matters? Are these photographic essays typically different from your research work?

Yes and No. For a while I had this rhythm where I would get hired as a human rights research consultant to spend a month or longer in a country, working with a specific community about a very specific human rights or public health issue and while working on the project I would inevitably form personal relationships that would then tangentially inform my personal work in some way. Sometimes the subject matter of my personal work would correlate to my consulting work, but not always. I’m a big collaborator, so while documenting any group of people or community, I give space for them to have autonomy in defining the ultimate message that work conveys. And within that context, the work is also a reflection of my personal relationships. This was particularly true with Displaced Youth, the series I made in Ukraine with people/friends who had been displaced from the Russian invasion of Crimea. That project unfolded over a couple of years as I continued to meet incredible artists and musicians who warmly invited me into their world.

You also lived in Mozambique for a period of time and worked on a series of personal projects including Tech Girls Mahotas and Hotel Luso so can you tell me about the projects and your experiences at that time?

The irony is that I lived in Mozambique for 4 years from 04-08, but despite taking a lot of photos, I didn’t create work in the same way at that time – it was mostly portraits of friends and people that lived in my community. It wasn’t until 2014-18 that I made more focused work in Mozambique. I was on a contract with an organization there and was spending on average 5 months a year in Maputo, usually broken up into 6-8 weeks trips. It was during those years that I made Mahotas, Hotel Luso, and Tech Girls.

Mahotas was made with residents of a psychiatric hospital. I was working on a photovoice project that was examining the state of mental health services with clinical psychiatrists. Sadly, everyone was eager to show me just how terrible their clinic was, but there was one psychiatrist who quietly told me that she was quite proud of how her clinic operated. I visited the Mahotas clinic, which stood in contrast to the majority of psychiatric hospitals in Mozambique, extending its services beyond the standard in-patient psychosocial treatment to include a community reintegration program. This service included a form of occupational therapy in which patients are encouraged to engage in a range of activities including farming, gardening, animal husbandry, sewing, and artisanal crafting. The patients were excited to collaborate on a series, but I had some ethical concerns about how much they really understood the concept of publishing and exhibiting images. So together we came up with a way to protect their identity using an object, or in some cases an animal that is symbolic of their occupation within the hospital. The work was eventually exhibited as a solo show in Mozambique’s National Gallery in 2018.

Hotel Luso was a much more personal project for me, created with friends, some that I had known for over 10 years. Between 2005-08 I attended number of underground clandestine gay parties. The location would be announced at the last minute due to safety concerns. In those spaces I made some close friends, some of whom went on to found the first gay rights organization, an organization that the government still refuses to legally recognize. Mozambique is odd in that homosexuality is permissible by law, which keeps human rights lawyers at bay, however the social stigma is dangerously intense. To this end there are no gay spaces, no gay bars, no gay pride celebrations, and if an employer finds that someone is gay they can legally fire them, and with the advent of social media that happens more often. In 2017, while reconnecting with those same friends, they expressed interest in collaborating with me on a series that speaks to this dichotomy, but finding a way to tell that story was complicated. One morning I was walking through the “red light” district of Maputo, and struck up a conversation with the owner of a sex hotel. She told me that the hotel was mostly empty during daylight hours and I could rent the entire space for $6 an hour. I ran it by my friends, and they loved the idea of reclaiming and ultimately queerifying a space, particularly one where love is traditionally kept hidden. We rented the hotel several times over the course of a month. Participants brought with them flowers, lovers, and anything that aided in the kind of queer expression that is often denied to them in other spaces. A selection of this series was exhibited at RedHook Labs in 2018.

Hotel Luso – Daniel Jack Lyons

Also, most recently a project you’ve been working on in the Amazonian rain forest that speaks to both climate change and the rise of right wing authoritarianism?

Exactly, that’s the project I am immersed in now, and working on making into a monograph. This project began as a collaboration with Thiago Carvalo, a brazilian land activist and youth organizer. Thiago founded an organization called Casa Do Rio, which was initially intended to be an artist space to host residencies, but he received funding to focus on youth leadership programs, and that has been the organizations focus for the last 10 years. He came across my series, Displaced Youth and appreciated the way that series portrayed positive images of youth against a more somber socio-political backdrop. He hosted me as an artist in residence for 2 months in the summer of 2019. The process was pretty simple, it started with a big meeting of different groups of people – dancers, skaters, metal heads, etc. I presented a slide show of my work, introduced myself and the project. I explained that I work based on invitations and taped my number to the wall. Immediately my phone was exploding with messages and I didn’t stop for the entire 8 weeks. A lot of time was spent just hanging out with people long before I took out my camera. Everyone that participated chose how and where they wanted to be photographed, giving them autonomy in guiding the projects narrative. I was meant to go back this past summer and continue working on the series, however like so many things in 2020, plans changed.

Like a River – Daniel Jack Lyons

Now back to LA. How long have you been living in Laurel Canyon with your husband Nino and these beautiful dogs? And tell me about the area that of course is synonymous for its counterculture attitudes and has drawn in a multitude of creatives and musicians.

Technically I’ve lived in Laurel Canyon for 5 years, but I’ve only been in LA full time for the past 2 years. Laurel Canyon is cool. It’s got the obvious rich history of being home to Eric Burdon, the Byrds, Joni Mitchell, John Mayall, Brian Wilson, Neil Young, etc – I’m a big music nerd, so it’s appealing to me. But mostly I just love the peace and quiet. Especially after living in New York for so many years, Laurel Canyon makes me feel like I’m on an island of nature surrounded by an ocean of concrete.

And your beautiful mid-century home. When did you buy it? Did you make any major structural changes? I know you completely landscaped the whole garden?

My husband and I bought it in 2015. We haven’t touched anything inside the house. The only thing we’ve done is landscape the backyard, and create our dream garden. It’s been a fun process of slowly planting and playing in the dirt. My garden is a sanctuary to me, even in the winter I spend most of my time outside.

You’ve collected some beautiful furniture and artifacts as well, did you source most in Los Angeles, on your travels or both?

The house actually came with a lot of great mid century furniture. We acquired other things to fill the gaps from consignment and thrift stores here in LA. There are some artifacts from my travels scattered around, but most of the artwork, paintings, and pottery were all made by either family friends.

And your coffee table has become somewhat of an accidental shrine to your work?

Totally accidental! I probably shouldn’t say this, but I really don’t buy magazines anymore. So the only magazines and papers on the coffee table are the ones I’ve shot for!

I love your recent portrait of Paris Hilton for The New York Times and can imagine she was a rather unique subject matter?

Thank you so much. Yeah she was really kind, we mostly talked about dogs in between shots.

Any new ideas / projects in the pipeline? I’m presuming staying committed to exposing human rights, social justice and LGBTQ issues is something you’ll continue with?

I’m still really focused on my project in the Amazon, but in the last 2 years since spending more time in LA I’ve been working on a project here. I shot two bodies of work for the New York Times since being in LA, one that explored a predominantly Latino punk and hard core scene on the peripheries of Los Angeles. And the other documented queer performance artists that orbited a monthly party called Club SCUM in East LA. The two scenes have a lot of overlap and I’ve continued shooting both groups since the initial work was published. I find that so much of my other work is very structured and focused, which is important, but it’s a wonderful reprieve to work on something that has no timeline or direction, just organic image making with friends and their friends. And in doing so it’s opened up the opportunity for new directions in collaborating. For example, I recently created a project called ANIMA with a performance artist named DVVSK for Atmos. I initially met DVVSK while shooting the Club SCUM performers. We’ve stayed connected and over the first lockdown we came up with an idea for a project about becoming nature. I’m currently exploring other collaborations for publications with more people form that group as well. I’ve definitely found my queerdo community here in LA. But yes, I will always be committed to aligning my work with themes of social justice, human rights, and particularly LGBTQ liberation. I couldn’t change that if I tried, it’s in my DNA.