Pot Dealer

What happens when ideas get out of hand? I asked Ben Sanders, who has made quite a commercial and fine art career for himself here in LA by focusing on no set discipline, because he’s cool like that. He chooses instead to ride the endless wave of whatever piques his interest.

And by whatever, we mean quotidian fare like bonsai, bottle caps, gardening, and cooking. Sanders twists these subjects into multidisciplinary works of rare, captivating sights. Among these, landscape paintings of surreal gradient forms hovering over a fixed horizon that depict post-human realities. He’s also started personal projects that have escalated into large scale bodies of work, including 300 painted planter pots and 200 bonsai drawings. Not to mention his long standing relationship with large replicas of bottle tops.

He’s visionary in his will to allow opposing ideas to coexist indefinitely. By being both obsessive and open in his practice, Sanders has made a reality out of the illusion that fine art and commercial work can carry on symbiotically.

Tell us what it’s like growing up as a local on the Eastside of Los Angeles?

I grew up on the border of a number of different suburban towns east of LA: Temple City, Arcadia, San Gabriel, Pasadena, and Sierra Madre. All of these places feel like small towns anywhere in America, but are only a short drive away from Los Angeles proper. My dad has been a metal fabricator for my whole life, and for most of it has worked in Hollywood building sets. He worked on locations, on sets, and in his fabrication shop in Pasadena. My mom was at home for most of my childhood. We lived on a quiet dead-end street in Temple City. Our quiet suburban existence was punctuated each weekend with excursions into the city with friends, usually to go to concerts or wander up and down Melrose.

“Making works of art gives me that outlet to be able to explore freely, without limits or parameters.”

Your father is a metalsmith who must have had a huge influence on you in your early years. Did that exposure to Hollywood sets being fabricated at the time guide you to head into the arts?

I watched my father build and run his own business perfecting a craft that he loved. He always communicated to me that, even with the ups and downs that come with that life, the happiness and meaning found in doing what you love everyday is worth it. My parents were never hostile to the idea of going to art school or pursuing a creative career, because they were quite familiar with it themselves. I remember the parents of a lot of my high school friends were very against them trying to go into a creative field, because they didn’t think it would be a stable career. I never had that problem. I was always very encouraged by my family to pursue art, which I had always shown a proclivity for.

What type of work were you creating whilst studying at Art Center College of Design and what was your plan after graduating?

I went to the Art Center for Illustration, so at first I was doing your typical figure drawing, oil painting, etc.—learning technical skills. As I was finishing up there, I started doing editorial illustration work for the New York Times, Bloomberg, and other publications. I took every penny I had and went to New York the summer before my final semester and passed my book around to art directors. During my final semester at Art Center, I was doing an illustration job about once a week. All the while, I was still making paintings when I was not working on jobs.

You’ve worked across multiple creative disciplines. Tell us about this journey and how you’ve landed on mainly painting and sculptural work?

Even when I was at Art Center doing commercial art, I knew I wanted to make artwork and show it. There is an ambiguity that comes with making art and showing it that doesn’t exist in illustration, where the primary objective is clear communication. I also knew that the only way I would be really happy is if I was able to (for the most part) make whatever I wanted. Making works of art gives me that outlet to be able to explore freely, without limits or parameters. That being said, I still adore applied arts: design, illustration, etc. As a consumer/viewer, I think I am actually more inclined to that stuff than to fine art.

Your influences come from the everyday—gardening, cooking, collecting, painting, parenting, bartending. This is all reflected in your output, correct?

Yes, I make work about all of these things because I am naturally interested in them and it makes sense to bring those interests into the studio. Making art is a long game, a lifetime pursuit. I have to keep it interesting for myself. There is also a mental and emotional framework surrounding the making of art in the studio that I find helpful to apply to other aspects of life, like gardening, bonsai, cooking, etc. This sort of intense, self-guided focus, with an emphasis on learning by doing, can be very helpful to apply to other aspects of life. So I would say that both realms, “the studio” and “life” are equally influenced by each other.

“I was reading a lot about the far past and the far future.”

You’ve worked across multiple creative disciplines. Tell us about this journey and how you’ve landed on mainly painting and sculptural work?

Even when I was at Art Center doing commercial art, I knew I wanted to make artwork and show it. There is an ambiguity that comes with making art and showing it that doesn’t exist in illustration, where the primary objective is clear communication. I also knew that the only way I would be really happy is if I was able to (for the most part) make whatever I wanted. Making works of art gives me that outlet to be able to explore freely, without limits or parameters. That being said, I still adore applied arts: design, illustration, etc. As a consumer/viewer, I think I am actually more inclined to that stuff than to fine art.

Your influences come from the everyday—gardening, cooking, collecting, painting, parenting, bartending. This is all reflected in your output, correct?

Yes, I make work about all of these things because I am naturally interested in them and it makes sense to bring those interests into the studio. Making art is a long game, a lifetime pursuit. I have to keep it interesting for myself. There is also a mental and emotional framework surrounding the making of art in the studio that I find helpful to apply to other aspects of life, like gardening, bonsai, cooking, etc. This sort of intense, self-guided focus, with an emphasis on learning by doing, can be very helpful to apply to other aspects of life. So I would say that both realms, “the studio” and “life” are equally influenced by each other.

On the commercial side, you’ve had the opportunity to work with mega brands primarily producing large scale murals. How did this come about? And what’s the process in painting gradients on such a large scale?

I started painting these huge gradient murals, and word spread. I don’t advertise it or anything, it’s all word of mouth. I’ve done them for Nike and Louis Vuitton. Doing these murals has supported my studio and allowed me to keep making art. That’s the story of my career so far: the applied arts support the “fine” arts. (That is a strictly materialist interpretation, because philosophically I don’t recognize a distinction there.) A lot of artists have day jobs to support their practice. I am no different, it’s just that my day job has been commercial art.

I'm a big fan of your 'Pot Dealer' and ‘Bonsai' projects, which have also been turned into beautiful publishing projects. Tell us briefly about both.

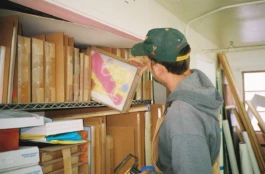

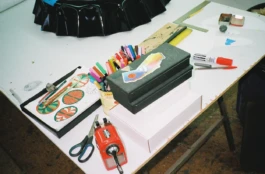

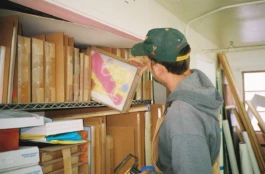

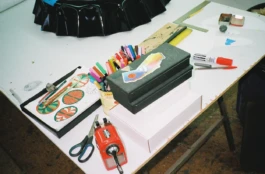

Those are both projects that started on a whim and got out of hand. My painted pots were little novelties I marketed via Instagram and sold for cheap. I kept making more and more, and suddenly I had made like 300. My friend Elana Schlenker, an amazing designer, helped me design a catalog of the pots. We still have to make the second volume. I published it myself through my studio. I think Martin Kippenberger [German artist of multiple disciplines] once said that artists shouldn’t wait for someone else to publish their work, but should just do it themselves. I took that to heart. The Bonsai were the same way, I just started drawing them while my daughter was taking her naps, and all of the sudden I had 200 of them. That book was published by Ampersand in Portland, and designed by Benjamin Critton, who co-founded Marta with his partner, Heidi Korsavong.

You have a great relationship with OCHI Gallery and recently exhibited ‘Deep Time’ that consisted of striking scenes of highly-rendered earthscapes. Where did the idea for this show come from?

I published a little booklet of source material with the guys at First Last, where you can see all of the diverse imagery that informed that show. Long story short, that show was about making work that represented a world after humanity. I was reading a lot about the far past and the far future. I wanted the show to reflect an awe for the physical world, from an atom to a galaxy.

You have an upcoming show, “New Caps,” which opens at Marta gallery in June. Can you unveil the artistic process behind this new series of oversized bottle tops? We understand your fabricating these alongside your father. That must be a very special experience collaborating together.

The bottle caps are another ongoing series. I have been making them since 2014. Up until recently I have painted imagery on them that I appropriated from other stuff, like packaging, ephemera, the internet, etc. The newest ones are painted with my own imagery. They are sort of an ode to my appreciation for commercial graphics, type, and illustration. Either by focusing and honoring a found image, or translating my own imagery into a graphic form.

The structures themselves are punched out of sheet metal with a giant hydraulic metal working machine in my dad’s shop. We have been perfecting their production the whole time, with each batch getting better. It’s very fun to make them with him, and to work in the shop for a few days whenever we produce a batch. I worked in his shop all throughout my childhood, so it’s nice to go back to that every once and a while. I have also steadily improved my paint technique with every batch, and they are becoming more and more slick and perfect.

The show at Marta will be really special because Marta and my gallery, OCHI, co-published a survey of all the caps I have made so far. There are pictures of my dad and I making them in the book, which I love.

bensandersstudio.com

@bensandersstudio

Ben Sanders 'Bottle Caps' book available here

Pot Dealer

What happens when ideas get out of hand? I asked Ben Sanders, who has made quite a commercial and fine art career for himself here in LA by focusing on no set discipline, because he’s cool like that. He chooses instead to ride the endless wave of whatever piques his interest.

And by whatever, we mean quotidian fare like bonsai, bottle caps, gardening, and cooking. Sanders twists these subjects into multidisciplinary works of rare, captivating sights. Among these, landscape paintings of surreal gradient forms hovering over a fixed horizon that depict post-human realities. He’s also started personal projects that have escalated into large scale bodies of work, including 300 painted planter pots and 200 bonsai drawings. Not to mention his long standing relationship with large replicas of bottle tops.

He’s visionary in his will to allow opposing ideas to coexist indefinitely. By being both obsessive and open in his practice, Sanders has made a reality out of the illusion that fine art and commercial work can carry on symbiotically.

Tell us what it’s like growing up as a local on the Eastside of Los Angeles?

I grew up on the border of a number of different suburban towns east of LA: Temple City, Arcadia, San Gabriel, Pasadena, and Sierra Madre. All of these places feel like small towns anywhere in America, but are only a short drive away from Los Angeles proper. My dad has been a metal fabricator for my whole life, and for most of it has worked in Hollywood building sets. He worked on locations, on sets, and in his fabrication shop in Pasadena. My mom was at home for most of my childhood. We lived on a quiet dead-end street in Temple City. Our quiet suburban existence was punctuated each weekend with excursions into the city with friends, usually to go to concerts or wander up and down Melrose.

“Making works of art gives me that outlet to be able to explore freely, without limits or parameters.”

Your father is a metalsmith who must have had a huge influence on you in your early years. Did that exposure to Hollywood sets being fabricated at the time guide you to head into the arts?

I watched my father build and run his own business perfecting a craft that he loved. He always communicated to me that, even with the ups and downs that come with that life, the happiness and meaning found in doing what you love everyday is worth it. My parents were never hostile to the idea of going to art school or pursuing a creative career, because they were quite familiar with it themselves. I remember the parents of a lot of my high school friends were very against them trying to go into a creative field, because they didn’t think it would be a stable career. I never had that problem. I was always very encouraged by my family to pursue art, which I had always shown a proclivity for.

What type of work were you creating whilst studying at Art Center College of Design and what was your plan after graduating?

I went to the Art Center for Illustration, so at first I was doing your typical figure drawing, oil painting, etc.—learning technical skills. As I was finishing up there, I started doing editorial illustration work for the New York Times, Bloomberg, and other publications. I took every penny I had and went to New York the summer before my final semester and passed my book around to art directors. During my final semester at Art Center, I was doing an illustration job about once a week. All the while, I was still making paintings when I was not working on jobs.

You’ve worked across multiple creative disciplines. Tell us about this journey and how you’ve landed on mainly painting and sculptural work?

Even when I was at Art Center doing commercial art, I knew I wanted to make artwork and show it. There is an ambiguity that comes with making art and showing it that doesn’t exist in illustration, where the primary objective is clear communication. I also knew that the only way I would be really happy is if I was able to (for the most part) make whatever I wanted. Making works of art gives me that outlet to be able to explore freely, without limits or parameters. That being said, I still adore applied arts: design, illustration, etc. As a consumer/viewer, I think I am actually more inclined to that stuff than to fine art.

Your influences come from the everyday—gardening, cooking, collecting, painting, parenting, bartending. This is all reflected in your output, correct?

Yes, I make work about all of these things because I am naturally interested in them and it makes sense to bring those interests into the studio. Making art is a long game, a lifetime pursuit. I have to keep it interesting for myself. There is also a mental and emotional framework surrounding the making of art in the studio that I find helpful to apply to other aspects of life, like gardening, bonsai, cooking, etc. This sort of intense, self-guided focus, with an emphasis on learning by doing, can be very helpful to apply to other aspects of life. So I would say that both realms, “the studio” and “life” are equally influenced by each other.

“I was reading a lot about the far past and the far future.”

You’ve worked across multiple creative disciplines. Tell us about this journey and how you’ve landed on mainly painting and sculptural work?

Even when I was at Art Center doing commercial art, I knew I wanted to make artwork and show it. There is an ambiguity that comes with making art and showing it that doesn’t exist in illustration, where the primary objective is clear communication. I also knew that the only way I would be really happy is if I was able to (for the most part) make whatever I wanted. Making works of art gives me that outlet to be able to explore freely, without limits or parameters. That being said, I still adore applied arts: design, illustration, etc. As a consumer/viewer, I think I am actually more inclined to that stuff than to fine art.

Your influences come from the everyday—gardening, cooking, collecting, painting, parenting, bartending. This is all reflected in your output, correct?

Yes, I make work about all of these things because I am naturally interested in them and it makes sense to bring those interests into the studio. Making art is a long game, a lifetime pursuit. I have to keep it interesting for myself. There is also a mental and emotional framework surrounding the making of art in the studio that I find helpful to apply to other aspects of life, like gardening, bonsai, cooking, etc. This sort of intense, self-guided focus, with an emphasis on learning by doing, can be very helpful to apply to other aspects of life. So I would say that both realms, “the studio” and “life” are equally influenced by each other.

On the commercial side, you’ve had the opportunity to work with mega brands primarily producing large scale murals. How did this come about? And what’s the process in painting gradients on such a large scale?

I started painting these huge gradient murals, and word spread. I don’t advertise it or anything, it’s all word of mouth. I’ve done them for Nike and Louis Vuitton. Doing these murals has supported my studio and allowed me to keep making art. That’s the story of my career so far: the applied arts support the “fine” arts. (That is a strictly materialist interpretation, because philosophically I don’t recognize a distinction there.) A lot of artists have day jobs to support their practice. I am no different, it’s just that my day job has been commercial art.

I'm a big fan of your 'Pot Dealer' and ‘Bonsai' projects, which have also been turned into beautiful publishing projects. Tell us briefly about both.

Those are both projects that started on a whim and got out of hand. My painted pots were little novelties I marketed via Instagram and sold for cheap. I kept making more and more, and suddenly I had made like 300. My friend Elana Schlenker, an amazing designer, helped me design a catalog of the pots. We still have to make the second volume. I published it myself through my studio. I think Martin Kippenberger [German artist of multiple disciplines] once said that artists shouldn’t wait for someone else to publish their work, but should just do it themselves. I took that to heart. The Bonsai were the same way, I just started drawing them while my daughter was taking her naps, and all of the sudden I had 200 of them. That book was published by Ampersand in Portland, and designed by Benjamin Critton, who co-founded Marta with his partner, Heidi Korsavong.

You have a great relationship with OCHI Gallery and recently exhibited ‘Deep Time’ that consisted of striking scenes of highly-rendered earthscapes. Where did the idea for this show come from?

I published a little booklet of source material with the guys at First Last, where you can see all of the diverse imagery that informed that show. Long story short, that show was about making work that represented a world after humanity. I was reading a lot about the far past and the far future. I wanted the show to reflect an awe for the physical world, from an atom to a galaxy.

You have an upcoming show, “New Caps,” which opens at Marta gallery in June. Can you unveil the artistic process behind this new series of oversized bottle tops? We understand your fabricating these alongside your father. That must be a very special experience collaborating together.

The bottle caps are another ongoing series. I have been making them since 2014. Up until recently I have painted imagery on them that I appropriated from other stuff, like packaging, ephemera, the internet, etc. The newest ones are painted with my own imagery. They are sort of an ode to my appreciation for commercial graphics, type, and illustration. Either by focusing and honoring a found image, or translating my own imagery into a graphic form.

The structures themselves are punched out of sheet metal with a giant hydraulic metal working machine in my dad’s shop. We have been perfecting their production the whole time, with each batch getting better. It’s very fun to make them with him, and to work in the shop for a few days whenever we produce a batch. I worked in his shop all throughout my childhood, so it’s nice to go back to that every once and a while. I have also steadily improved my paint technique with every batch, and they are becoming more and more slick and perfect.

The show at Marta will be really special because Marta and my gallery, OCHI, co-published a survey of all the caps I have made so far. There are pictures of my dad and I making them in the book, which I love.

bensandersstudio.com

@bensandersstudio

Ben Sanders 'Bottle Caps' book available here